European Central Bank QE: bricolage or extension?

This post is a bit long and, I am afraid, in some quantitative parts a little complex. So, for impatient readers, let me present here its main conclusions. To deal with the scarcity of bonds to buy under its QE program, the ECB could do some bricolage, changing some of the constraints it has imposed on the purchases. I examine instead in this post the case in which the ECB would extend its purchases to equities and/or bank loans when prolonging its purchase program (or enlarging it for that matter). With this extension, the physical constraint on assets to be purchased, on which market observers are concentrating their attention, would loose its urgency. Both asset classes provide quite large amounts to be purchased. The sheer amounts available for the two asset classes, 6 trillion for equities and nearly 12 trillion for bank loans, have to be substantially reduced to get realistic estimates of what the ECB could buy, in particular if it wished to stay close to the capital key in its operations. Still, the problem of not having enough assets to buy basically disappears when purchases are extended to one or the other asset class. The substitution of bonds with equities and/or bank loans while prolonging QE could be done in the same way across countries or could be concentrated in countries like Germany, Finland, Ireland, Netherland and Portugal, where the amount of sovereign bonds to be purchased is more limited.

The more important issue is what would be the economic effectiveness of a prolongation of the QE purchases assorted by an extension of the assets to be bought. My sense is that, from this point of view, the most effective addition would be equities, because the purchase of this asset class would work through a different channel, a reduction of the equity premium, than those mostly used so far: a recovery in bank lending and a compression of the yield curve.

So the answer to the question in the title is: Better Extension than Bricolage.

Market observers have been predicting since quite some time that the European Central Bank would have met difficulties with the implementation of its Quantitative Easing (QE) purchase programs. In particular, they expected that it would run out of German, but also Finnish, Dutch, Irish and Portuguese bonds to buy. Contrary to expectations, the ECB has been able so far to carry out smoothly its program. However, at the September press conference Draghi recognized that the program would need some adaptation. Most observers understood this to be connected to a possible announcement of the lengthening of the program beyond the announced date of March 2017: it would not make much sense to review at the end of 2016 a program that is expected to end in March of 2017. Draghi announced, in particular, that the relevant Committees were mandated to work to assure the continued smooth implementation of the program 1 . In his press conference in October, while not giving any hint about the possible changes, Draghi confirmed that changes are likely to come in December.

The ECB is quite good in avoiding leaks and thus we do not know in which directions the Committees are actually working. Not much phantasy is needed, though, to guess that they must be studying the possible relaxation of the constraints that the ECB fixed for its purchases:

- No purchases of securities with a yield to maturity lower than the deposit facility rate, currently -40 basis points,

- Purchases apportioned to different jurisdictions according to the capital key of the ECB,

- No further purchase of securities from a sovereign issuer when 33 per cent of its bonds would have been purchased (issuer limit),

- No purchase of a specific security when 33 per cent of its outstanding amount would have been purchased (issue limit).

The possible relaxation of these constraints should be, in my view, assessed against two criteria:

- Quantitative effectiveness, i.e. how much more space would they create for the ECB purchases?

- Cost, i.e. how costly would it be to relax the constraints, which obviously were set for some reason?

In terms of effectiveness, it is not clear to me that the relaxation of any of these constraints would easily allow adding another 9 months of purchases to the program, in order to extend it until the end of 2017. As I understand it, only with a combination of various options could the ECB comfortably prolong the ECB’s APP programme until the end of next year.

In terms of cost, my assessment is that it rises as we move from a relaxation of the issue limit, to a relaxation of the issuer limit, to the purchases of bonds with a yield lower than the deposit facility rate and up to the abandonment of the capital key, which would be the most costly. The cost issue is aggravated by the fact that, in order to extend the program by 9 months, it would be necessary to relax more than one constraint.

If the relaxation of the constraints brings limited effectiveness but significant costs, it is plausible that the Committees, and eventually the Governing Council, will also look at the possibility of extending the asset classes purchased under the program. After all, this would just further a trend followed so far by the ECB, which added one asset class after the other to its purchases: it started with covered bonds, then extended purchases to sovereign bonds, then to Asset Backed Securities, local government and international organization bonds and eventually to corporate bonds. Extending them further to another asset class should not be so surprising. Instead of engaging in bricolage the ECB could just extend the QE program to new asset classes.

An additional reason for adding asset classes to the purchases is that this would attenuate the negative consequences that a concentration of QE on bonds, ad in particular sovereign bonds, is causing. These negative consequences have manifested themselves recently in the repo market, which is operationally disturbed by the huge amount of bonds frozen in €-area central banks portfolios. The negative consequences extend to the fact that pricing in the bond market is dominated by a large, price insensitive buyer like the ECB. In addition, the compression of the yield curve as well as of the spreads between different sovereigns has gone very far and it is not obvious that a further compression would be either possible or desirable.

If one looks at the €-area financial market there is not that many other asset classes with sufficient size for a purchase appetite as voracious as that of the ECB. I would exclude both bank bonds, either senior or junior, because I think the ECB has already put so many of its policy assets in the banking basket, that it is not willing to add more. In addition, the purchases by the ECB of bonds from entities it supervises would rightly be seen as awkward. I would also exclude, with even more determination, foreign assets, because a purchase program by the second most important global central bank of foreign securities, mostly dollars, would be, rightly, interpreted as a declaration of a currency war that the ECB would be very loath to issue. What is left is equities and bank loans.

The quantitative evidence of purchases in these two segments as well as the advantages and disadvantages of extending QE to them is examined in turn.

Equities

The size of the €-area equity market is, as it can be seen in Column (1) of table 1, more than 6 trillion euro. On the face of it, this provides huge space for ECB purchases. However, for the reasons mentioned above, the ECB would probably be reluctant to include bank equities in its purchases. If an estimate of bank equities is excluded, the total size of the € area market is reduced to 5.5 trillion, still a more than comfortable playground for the ECB purchases. This total is distributed across the largest 15 jurisdictions of the €-area 2 as reported in Column (2) of Table 1. A comparison between the shares of the national equity markets over the total, in Column (3), and the ECB capital key, in Column (4), shows that there are quite significant differences. For instance, the share of the Italian equity market over the total is about a half of the share of Banca d´Italia in the capital of the ECB. The opposite happens for the Netherlands. To take into account that equity markets in some countries are small relative to the share of the relevant central bank in the ECB capital key, equity purchases would have to be scaled down if the ECB wanted to apportion them according to the capital key. The scaling down exercise, which is carried out in Column (6), gives an estimate of the maximum amount of equities that the ECB could purchase in the different jurisdictions while closely (but not perfectly) respecting the capital key.3

Table 1: Euro area stock market capitalisation and ECB potential purchases based on the capital key.

| Countries | Stock market capitalisation (€ bn) | Stock market capitalisation excluding financials

(€ bn) |

Share in total stock market

(%) |

Normalized ECB capital key (%) | Scaling factor | Potential purchases of equities

(€ bn, based on PT) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| France | 1918.2 | 1726.4 | 31.40 | 20.78 | 8.13 | 402.3 |

| Germany | 1576.0 | 1418.4 | 25.80 | 26.37 | 10.32 | 510.6 |

| Spain | 723.1 | 650.8 | 11.84 | 12.95 | 5.07 | 250.8 |

| Netherlands | 669.1 | 602.2 | 10.95 | 5.87 | 2.30 | 113.6 |

| Italy | 483.7 | 435.4 | 7.92 | 18.04 | 7.06 | 349.3 |

| Belgium | 380.8 | 342.7 | 6.23 | 3.63 | 1.42 | 70.3 |

| Ireland | 117.6 | 105.8 | 1.92 | 1.70 | 0.67 | 32.9 |

| Austria | 88.3 | 79.4 | 1.44 | 2.88 | 1.13 | 55.7 |

| Portugal* | 55.0 | 49.5 | 0.90 | 2.55 | 1.00 | 49.5 |

| Luxembourg | 43.3 | 39.0 | 0.71 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 5.8 |

| Greece* | 38.7 | 34.8 | 0.63 | 2.98 | 1.17 | 34.8 |

| Slovenia* | 5.5 | 5.0 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 5.0 |

| Slovakia* | 3.5 | 3.1 | 0.06 | 1.13 | 0.44 | 3.1 |

| Malta | 4.0 | 3.6 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 1.8 |

| Cyprus* | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 2.2 |

| Euro area | 6109.2 | 5498.3 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1887.8 |

Source: Worldbank and World Federation of Exchanges and ECB; data available end-2015 for all countries except Italy (end-2014) and Slovakia (end-2013); data missing for Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania; (1) We used the end-of year exchange rate from USD to EUR. (2) We assumed the share of financials to be 10% in each country, based on the average share of financials in the four biggest EA stock exchanges; (3) We normalized the ECB capital key to exclude the small countries for which we could not find equity data; (5) This is the ratio of the share of the ECB’s normalized capital key of country i over the ECB capital share of Portugal, chosen among those with a low ratio between market capitalisation and capital key; (6) Calculated as the market capitalisation of Portugal multiplied by Column (5) except for Greece, Slovenia, Cyprus and Slovakia, marked with an asterisk, for which the amount that could be purchased is capped at the amount of non bank equities reported in Column (2).

The amounts of equities that the ECB could potentially purchase while remaining close to the capital key, as estimated in Column (6), are still very large, amounting to nearly 2 trillion euro. They have, however, to be taken with a pinch of salt, for two reasons.

First, the experience of the central banks, like the Banca d´Italia, that held equities in their investment portfolios, for instance in their pension fund, is that the central bank is sometimes embarrassed by the need to exercise its shareholders rights, for instance in the case of a hostile bid on a company. One way to attenuate these problems would be for the central bank to hold equities indirectly through Exchange Traded Funds. Following this line of reasoning, the relevant figure for the possible ECB equity purchases would seem to be the size of the equity ETF funds in the euro area.

I am going to argue below that this line of reasoning is not totally correct. Still let me present some evidence about the equity ETF market in Europe.

A publication at the beginning of this year 4 sized the European equity ETF 5 at the end of 2015 at around 320 billion euro, having grown by an average of 16 per cent per annum in the previous 4 years. The same rate of growth was expected for 2016, bringing the total expected for the end of 2016 to some 370 billion €. Overall this information indicates that the European equity ETF market is quite large and growing at a very brisk pace, consistently with what is happening at global level.

However, as I mentioned, it would not be correct to conclude that the ECB purchases in the equity market under the form of ETF would be limited by the existing size of the ETF. Indeed what could happen, along the line of what happened with the purchases by the Bank of Japan, is that the market would just assemble ETF in the form and shape desired by the ECB. We can thus take the large size and the brisk growth of equity ETF just as an indication of the ability of the market to adapt supply to the possible demand of the ECB, with the only real constraints being the amount of underlying shares, as calculated in table 1.

The second reason to take the figures in Column (6) of Table 1 as a first indication only has to do with the experience of the Bank of Japan (BoJ), suggesting that too large purchases relative to the size of the market may produce undesired results. The BoJ began its ETF purchases in October 2010, buying 450 billion yen annually. The rate was doubled to 1 trillion yen a year in 2013, increased to 3 trillion a year in 2014, and to 6 trillion yen in 2016. As the amounts increased, equities purchases moved from being qualified as part of so called “qualitative” easing into “quantitative” easing.

The BoJ buys ETFs that track the TOPIX, the Nikkei 225 Stock Average, and the JPX-Nikkei 400. The proportions of the total purchases accounted for by these three indexes have been based on market capitalization: respectively, 54%, 42%, and 4%. The BoJ is limited to holding no more than 50% of any ETF. Market estimates are that the BoJ’s indirect holdings of TOPIX stocks will reach 3.25% of market cap by the end of the year. The BoJ has eligibility criteria for indices regarding creditworthiness, diversification of the portfolio and marketability. The BoJ does not buy ETF shares that are on the market. When it places an order for an ETF, the ETF share is newly created by an asset management company, using a basket of shares purchased by a securities company. Thus the BoJ is not limited by the outstanding volume of ETFs in the market.

The equity purchases by the BoJ have been criticized in the market because of distorting market functioning. Basically this distortion would derive from the size of purchases and from the specific modalities of BoJ purchases. As regards the first aspect, BoJ purchases are large with respect to the turnover in the Japanese equity market. As regards the second aspect, some problems came from the fact that the BoJ did not buy strictly according to market capitalization. Criticisms about the purchases by the Bank of Japan have been muted more recently, also because the Bank of Japan has modified the modalities of its purchases.

More generally, an amount of “distortion” from purchases is welcome. In a way central banks always aim at “distorting” conditions in the financial market with their actions. If we call the effect of central bank measures “macroeconomic effectiveness” instead of “distortion”, the welfare perception of the purchases is diametrically changed. For instance, in the case of the Bank of Japan, purchases were clearly aimed at supporting stock market prices and were assessed according to this criterion.

In order to evaluate the possible extension of ECB QE to shares and its possible effects it is useful to get a sense of the possible size of ECB purchases.

Table 2: A possible ECB equity purchase program.

| Countries | Max amount of equities available ( € bn ) |

Normalized capital key (%) |

Potential purchases of 20 bn/month

( € bn ) |

Share of purchases in total market (%) |

| (1) | (2) | (3)=240x(2) | (4) | |

| France | 402.3 | 20.78 | 49.9 | 2.9 |

| Germany | 510.6 | 26.37 | 63.3 | 4.5 |

| Spain | 250.8 | 12.95 | 31.1 | 4.8 |

| Netherlands | 113.6 | 5.87 | 14.1 | 2.3 |

| Italy | 349.3 | 18.04 | 43.3 | 9.9 |

| Belgium | 70.3 | 3.63 | 8.7 | 2.5 |

| Ireland | 32.9 | 1.70 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| Austria | 55.7 | 2.88 | 6.9 | 8.7 |

| Portugal | 49.5 | 2.55 | 6.1 | 12.4 |

| Luxembourg | 5.8 | 0.30 | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Greece | 34.8 | 2.98 | 7.2 | 20.6 |

| Slovenia | 5.0 | 0.51 | 1.2 | 24.4 |

| Slovak Republic | 3.1 | 1.13 | 2.7 | 86.7 |

| Malta | 1.8 | 0.09 | 0.2 | 6.3 |

| Cyprus | 2.2 | 0.22 | 0.5 | 23.9 |

| Euro area | 1887.8 | 100.00 | 240.0 | 4.4 |

Source: see Table 1; data missing for Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania. We assume purchases to follow the normalized capital key as shown in Column (2).In Column (4), we calculate the share of potential purchases over the market capitalisation of each country, excluding financials, as estimated in Table 1 Column (2).

In the exercise carried out in table 2 it is assumed, in Column (3), that, as from January 2017 and until the end of the year, the ECB substitutes 20 billion € of QE purchases of bonds with equities, in the form of ETF. This gives total purchases by the end of the year of 240 billion, which is 4.4 per cent of the total of outstanding non-bank equity in the €-area, as estimated in Column (2) of table 1. We cannot, however, take this percentage as a measure of the possible effect of purchases on the equity market, possibly in comparison with the 3.25 estimated for the BoJ purchases. As mentioned above, the €-area equity market is not integrated enough for this conclusion.

A complementary exercise is to compare the purchases in Column (3) of table 2, which would result by applying the 240 billion of purchases to the ECB capital key, with the amounts in Column (2) of table 1, i.e. the equities of non-financial corporations outstanding in the different national markets. This is done in Column (4) of table 2, reporting the share of each national market that would be bought if 240 billion were bought in the aggregate. Of course in the case of the countries with a small equity market, a large share of the outstanding amount would have to be bought, for instance in the case of Slovakia nearly 90 per cent of the total would have to be bought to respect the capital key. Symmetrically, in countries with a relatively large equity market only a small share of the market would be bought. For instance, in the Netherlands only 2.3 per cent of the outstanding equities would be bought. To avoid purchasing too large shares of the market in countries with small equity segments, the capital key should be applied flexibly in their case. However, in any case the bulk of the program would be carried out in the largest markets and an adaptation to the smallest ones would be relatively easy.

There are two conclusions that can be drawn from the quantitative evidence produced so far:

- Sizable purchases, e.g. 20 billion per month, are possible extending the QE program to equities while maintaining the amounts to be bought relatively small with respect to the non-financial equity market and remaining close to the ECB capital key;

- A flexible application of the capital key would be needed in the case of countries with small equity markets.

Of course the quantitative aspect of a possible program of purchase of equities is important, but is not the only relevant one.

More generally, it is necessary to assess advantages and disadvantages of an equity purchase program.

Among the advantages, I think one is very important: the ability of the program to compress the equity premium. Some of the criticisms about the effectiveness of the ECB QE program, and especially of a possible extension of it, is that it does not seem either possible, or desirable, to compress further the very low level of the yield curve by reducing the maturity premium. Neither does it look desirable to compress further the spread between different sovereign bonds. Lowering the equity premium could be a welcome differentiation for the effects of the ECB action.

Taking the behaviour of the Price/Earnings ratio as a very rough approximation to the behaviour of the equity premium, one can see in figure 1 that equities are valued, since the end of 2014, at the highest level since the beginning of the Great Recession in 2007, relative to earnings. Still, at around 15, the P/E ratio is quite lower than before the crisis and liable at being pushed higher by ECB purchases, because of a reduction of the equity premium.

One can argue that, so far, ECB action pushed the yield on corporations’ debt very low but that their overall cost of capital has remained high, with negative consequences on investment, because of the elevated cost of equity. A compression of the equity premium could thus complement the action of the ECB in promoting higher investment.

Figure 1: Price-earning ratio in the Euro area.

Source: IBES, Price/Earnings 12 months forward, Eurostoxx.

Yet another advantage that equity purchases would bring is a beneficial portfolio effect for central bank balance sheets that are currently very heavily concentrated on interest rate and sovereign risk: it makes sense, from a diversification approach, for central banks to hold equity risk, which should show little correlation with bond risk.

An obvious disadvantage of equities purchases, which could discourage fainthearted central bankers (one may wonder, though, whether there are any left, given the bravery they displayed since August 2007), is the risk for the income statement of central banks from holding volatile equities.

Another disadvantage, this time operational, is that equities are not, since many years, in the ECB collateral pool, thus central banks do not have familiarity with this market, except for those that invest part of their own funds in this asset class. However, this disadvantage could be dealt with by having recourse to agents doing the purchases for the ECB, analogously to what is currently done for purchases into another market with which central banks are not familiar: that of ABS.

In conclusion, instead of doing bricolage with the constraints of the QE program, the ECB could substitute a significant part of its bond purchases with equity purchases, in the form of ETF, without a fear of affecting market functioning but still reducing the equity premium and therefore extending beyond the bond market the “portfolio balance effect”, which is the transmission mechanism of QE. In order to take into account the different sizes of the equity market in different €-area countries, the ECB should apply the capital key to its purchases in a flexible way, in particular in small markets. Indeed I see no particular reason why the composition of the ECB purchases between the different assets it purchases should be the same in all €-area countries. For instance, the difficulties in purchasing German sovereign securities could be alleviated by purchasing German shares without necessarily buying a relatively large share of equities in countries, like Slovakia, which have a very small equity market. Similarly, purchases in the small Italian equity market could be relatively limited as the availability of Italian sovereign bonds is, alas, (over) abundant.

Bank Loans

On the face of it, bank loans provide practically unlimited amount of assets that the ECB could purchase under its QE program. Indeed table 3 shows that the total amount of bank loans in the €-area is, in aggregate, 11.9 trillion. Table 3 shows also the distribution of this aggregate across the countries of the €-area as well across the different institutional sectors.

Table 3. Bank loans in the €-area. Billion €.

| Country | Corporates | Households | Insurance | Other financials | General Government | Total |

| Austria | 161 | 154 | 0 | 29 | 29 | 373 |

| Belgium | 119 | 160 | 5 | 59 | 37 | 380 |

| Cyprus | 21 | 21 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 48 |

| Germany | 927 | 1,558 | 5 | 156 | 354 | 3,000 |

| Estonia | 7 | 8 | – | 2 | 0 | 17 |

| Spain | 511 | 708 | 6 | 55 | 92 | 1,372 |

| Finland | 77 | 124 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 223 |

| France | 946 | 1,146 | 70 | 124 | 209 | 2,495 |

| Greece | 88 | 105 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 210 |

| Ireland | 54 | 90 | 0 | 21 | 6 | 171 |

| Italy | 793 | 622 | 4 | 233 | 264 | 1,916 |

| Lithuania | 8 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Luxembourg | 68 | 42 | 2 | 38 | 4 | 153 |

| Latvia | 7 | 5 | – | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Malta | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Netherlands | 389 | 454 | 20 | 275 | 60 | 1,198 |

| Portugal | 80 | 119 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 217 |

| Slovenia | 9 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 21 |

| Slovakia | 17 | 28 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 47 |

| Euro area | 4,287 | 5,365 | 114 | 1,028 | 1,089 | 11,883 |

The total includes loans to non-financial corporations, households, the public sector and financial corporations. But the ECB is unlikely to buy mostly small loans to households and loans to the public sector, which would add themselves to the large purchases of public bonds. It is also unlikely that the ECB would want to buy loans extended by banks to other financial corporations, as it may want to concentrate its effort on the real side of the economy.6 The first Column of table 3 shows that the loans to the non-financial corporations are still very large at nearly 4.3 trillion.

If the ECB would like to stay close to the ECB capital key in its purchases of bank loans, these amounts are still not really indicative of what could be purchased for reasons similar to those presented above about equities: columns (1) and (2) of table 4 show that the percentage distribution of loans to non financial corporations per country is different from the capital key of the ECB. A similar exercise to that carried out for equities is presented in Column (3) of table 4.

Table 4. Potential purchases of bank loans.

| Countries | Percentage of loans | Normalized capital key | Potential purchases of bank loans (€ bn based on Latvia) |

| ( % ) | (%) | ( € bn ) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Austria | 3.76 | 2.79 | 48 |

| Belgium | 2.77 | 3.52 | 61 |

| Cyprus | 0.50 | 0.21 | 4 |

| Germany | 21.63 | 25.57 | 443 |

| Estonia | 0.17 | 0.27 | 5 |

| Spain | 11.91 | 12.56 | 217 |

| Finland | 1.79 | 1.78 | 31 |

| France | 22.07 | 20.14 | 349 |

| Greece | 2.06 | 2.89 | 50 |

| Ireland | 1.27 | 1.65 | 29 |

| Italy | 18.50 | 17.49 | 303 |

| Lithuania | 0.20 | 0.59 | 10 |

| Luxembourg | 1.59 | 0.29 | 5 |

| Latvia | 0.16 | 0.40 | 7 |

| Malta | 0.11 | 0.09 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 9.07 | 5.69 | 98 |

| Portugal | 1.86 | 2.48 | 43 |

| Slovenia | 0.21 | 0.49 | 8 |

| Slovakia | 0.39 | 1.10 | 17 |

| Euro area | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1729 |

Source: Column (3) reports the amount of bank loans that could be bought by the ECB while approximately respecting the capital key. This is obtained by estimating the possible purchases in each country by multiplying the amount of bank loans available in Latvia by the ratio of each country share in the ECB capital to the Latvian share. Latvia is one of the countries with the smallest share of bank loans relative to its capital key.

The amount of bank loans that could be purchased by the ECB, while closely respecting the capital key, as estimated in column (3) of table 4, is still very large at 1.7 trillion. However, in our quest for the amount of bank loans that could be bought by the ECB, there is another perspective to get a realistic figure. A reasonable universe of bank loans that the ECB could buy is given by the bank loans that it takes as collateral, since they represent, in a way, la crème de la crème of bank loans, those that it would be easiest to add to the central banks portfolios.

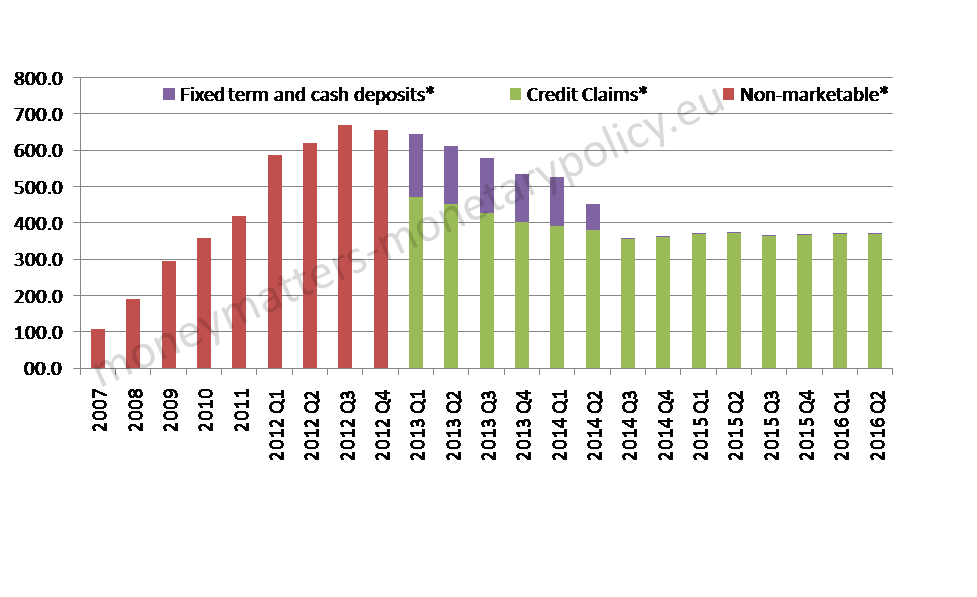

The time series of the credit claims used as collateral with the ECB is in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Credit claims used as collateral for ECB refinancing operations. Billion €.

Source: ECB. The break between Credit Claims and Fixed Term and Cash Deposits within the category of Non-Marketable collateral is only available since 2013.

In the chart one sees that, after having constantly grown since their introduction in 2007, credit claims used as collateral with the ECB reached a peak of nearly 500 billion at the beginning of 2013, but have come down to some 370 billion more recently. This fall is due to the fact that the recourse of banks to the funding from the ECB through temporary operations has come substantially down because of the large amounts of liquidity that the ECB now provides to bank by means of QE purchases. The amount of nearly half a trillion reached at the beginning of 2013 looks like a more reasonable estimate of the amount of bank loans that the ECB could potentially purchase than the current amount of 370 billion.

Unfortunately, the ECB does not publish data on the use of collateral per country, so we do not have a split of the possible purchases per country. In order to get an idea of what could be available in each country it is assumed in table 5, Column (1), that the percentage distribution per country of the bank loans used as collateral is the same as the distribution of overall credit claims to non-financial corporations. The same reasoning used for equities and bank loans, derived from the fact that the distribution of bank loans is different from that of the capital key, serves to scale down the possible purchases in Column (2) of table 5. This results in an amount of about 200 billion, which is a tiny fraction of the overall outstanding amount of bank loans, but is still an amount large enough to accommodate significant purchases by the ECB.

Table 5. Potential purchases of bank loans used as collateral in ECB operations.

| Credit claims

(1) |

Potential universe (bn)

(2) |

|

| Austria | 18 | 5 |

| Belgium | 13 | 7 |

| Cyprus | 2 | 0 |

| Germany | 102 | 49 |

| Estonia | 1 | 1 |

| Spain | 56 | 24 |

| Finland | 8 | 3 |

| France | 104 | 38 |

| Greece | 10 | 6 |

| Ireland | 6 | 3 |

| Italy | 87 | 33 |

| Lithuania | 1 | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 8 | 1 |

| Latvia | 1 | 1 |

| Malta | 1 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 43 | 11 |

| Portugal | 9 | 5 |

| Slovenia | 1 | 1 |

| Slovakia | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 473 | 190 |

For instance, the ECB could purchase 10 billion of bank loans in its purchase program for every month of 2017 and only buy about 60 per cent of the bank loans estimated in column (2) of table 5.

As in the case of the equities, the sheer quantitative availability of loans is not the end of the story: the advantages and disadvantages of purchasing bank loans are at least as important.

A clear disadvantage is that, unlike equities, the purchase of bank loans aggravates the concentration of the action of the ECB on banks, while it would be useful to broaden the ambit of the action to work through different channels. Indeed, as I documented in two previous posts, quite a lot has been done to surpass the two problems affecting bank lending: its overall scarcity and the very different conditions in the periphery with respect to the core. 7

Another disadvantage, this time of an operational nature, is that there is hardly any liquidity in the market for bank loans and, correspondingly, fixing a price for them is very difficult. The experience of purchases of Asset Backed Securities, which are also fairly illiquid, could attenuate but not eliminate this problem.

An advantage is that bank loans are already in the collateral pool and thus the implicit rule that only assets in the collateral pool are bought within the QE program would be respected.

Overall extending the program to equities and bank loans would deal with the “scarcity” problem, i.e. the difficulty for the ECB to find assets to purchase. The fact that equity purchases would broaden the action of the ECB from compressing the maturity premium to compressing the equity premium makes the extension to equities more appealing. Purchases of the two asset classes should not be seen, however, as mutually exclusive. Indeed to reduce the problems created by the concentration of purchases on bonds, one could very well envisage extending the program to both asset classes.

This post benefitted from useful information and assessments provided by Tetsuya Inoue and was prepared with the assistance of Pia Hüttl and Madalina Norocea. Remaining errors and imperfections are of course my own.

- “As regards implementation, there had to be no doubt about the Governing Council’s ability to act if needed. In this respect, the relevant committees should be tasked to evaluate options that ensured a smooth implementation of the APP. Potential revisions of the parameters had to take due consideration of their effectiveness from a monetary policy perspective.”[↩]

- We could not find data for some of the smallest countries in the €-area [↩]

- Portugal, as one of the countries with the smallest share of the equity market relative the capital key, is the country chosen to calculate the scaling down factor. Specifically the amount of non-bank equities outstanding in that country, which is obviously the maximum amount that can be purchased, is multiplied by the ratio between the share of each country in the capital key of the ECB and the share of Portugal, reported in column (5) to get the amount of potential purchases in the other jurisdictions. The estimates of the potential purchases in Column (6) depend heavily on the country chosen to calculate the scaling factor. For example, if Slovenia instead of Portugal was chosen the amount of potential purchases would halve to around 1 trillion. If Slovakia was chosen, thus assuring complete compliance with the capital key, potential purchases would be further reduced to only 450 billion.[↩]

- Marlène Hassine, Head of ETF Research, Lyxor Asset Management, European ETF Market -outlook for 2016. [↩]

- This included European non € countries, in particular the UK. We could not find information on only €-area aggregate.[↩]

- This is confirmed by the fact that the ECB does not take loans to financial corporations as collateral for its monetary policy operations. Different types of bank loans are accepted, including syndicated loans as well as RMDB (Retail Mortgage Backed Debt), i.e. residential mortgages or pools of credit claims, as well as so called Additional Credit Claims, i.e. bank loans that are only accepted by some central banks and have characteristics deviating from those of the bank loans that can be used all over the €-area. Non marketable asset is a general category, opposed to marketable asset, which includes credit claims (bank loans).[↩]

- The last of these two posts, written with Steve Donzè, can be found here: https://moneymatters-monetarypolicy.eu/bank-credit-supply-is-improving-in-the-e-area/ [↩]