Brexit has made the UK poorer: fact, no forecast from a “citizen of the world” expert.

One of the controversies that have followed the Brexit referendum, not the most important but not a trivial one either, is what are the effects of the decision to exit from the European Union on the UK economy.

Brexiteers poke fun at “experts”, mostly belonging to the “citizen of the world” category recently lambasted by the British Prime Minister, who forecast GDP losses because of Brexit. Brexiteers note that these losses are nowhere to be seen, indeed activity is holding up well post Brexit. Others would just add the two words “so far” to the previous conclusion. Somehow they would echo the exchange Ben Bernanke had with a US senator on September 24th 2008. The senator “had spoken to small-town bankers, auto dealers and others in his district with knowledge of the `real` U.S. economy. So far, he said, they had not seen any meaningful effects of the Wall Street troubles. `They will`, I said to him. `they will`.” 1

I tend to agree with the “so far” – “they will, they will” view, but this is not the issue I want to deal with in this post. I do not want to discuss forecasts, but just present a fact: Brexit has already made the UK poorer.

The bottom line of this post is that Brexit has imparted a negative shock to the purchasing power of the Brits that is more than half of that caused by the sheiks with the oil shock of 1973-1974.

To make my point I do not have to go any further than looking at a macroeconomic textbook. I have taken from my shelves an old version of Macroeconomics by Dornbusch and Fischer and read that with “…a worsening of the terms of trade – the price of exports relative to imports. Foreign goods become more expensive, thus reducing the purchasing power of the good we produce. Therefore our standard of living falls. ….The relative price of foreign goods in terms of domestic goods, the terms of trade, is then defined as:

eP*/P=terms of trade or relative price of imports

The term eP* measures the price of foreign goods in terms of dollars [i.e. national currency], and P of course measures the price of domestic goods in terms of dollars [i.e. national currency]. If import prices P* rise relative to domestic prices (P), we say there has been a worsening of the terms of trade. For example the repeated increases in oil prices worsened the importing countries` terms of trade and means that more units of exports…had to be given to buy a barrel of oil.”

The quotation by Dornbusch and Fischer also hints at an interesting comparison, i.e. looking at the terms of trade impact of Brexit against that of the oil shocks. Of course with the oil shocks it was the sheiks that imposed a loss of purchasing power on oil consumers, in Britain and elsewhere. With Brexit the loss is a self-inflicted wound. I have presented in a previous post why I think that Brexit should be defined, in Cipolla´s behavioural chart 2 , as a stupid action, i.e. an action that damages both its actor and his or her partner.

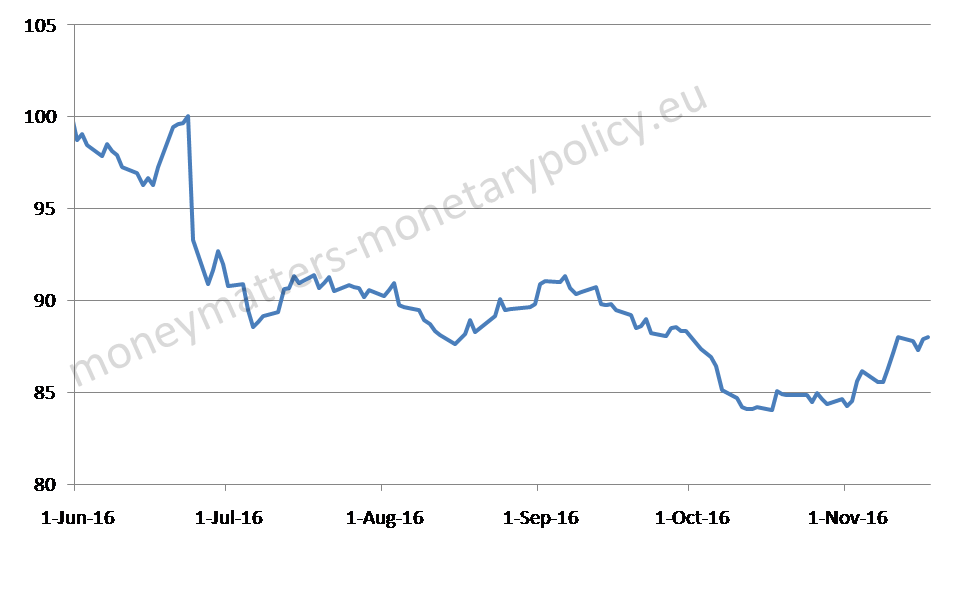

The empirical piece of evidence I need to complete my point is to look at what has happened to terms of trade with Brexit. We do not have as yet import and export prices (P* and P) for the post Brexit period, but we can assume that P* has not materially changed: global prices do not change because of a national event like Brexit 3. It is also unlikely that export price have changed a lot since the end of June. So the terms of trade are still dominated by changes in the exchange rate. And we know pretty well what has happened to it! Still it may be useful to recall it here: figure 1 reports the effective exchange rate of sterling with the level on June 1st at 100. Here we see a depreciation of about 13 per cent, which, for unchanged P and P*, corresponds to a 13 per cent deterioration of the terms of trade.

Figure 1. Effective exchange rate of sterling. June 23rd =100.

Source: BOE.

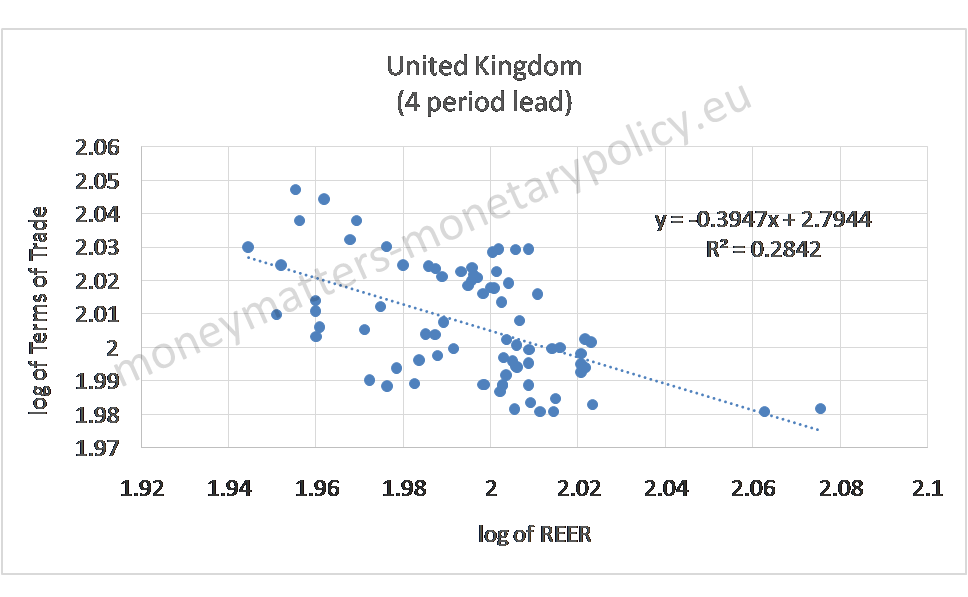

To check empirically the correlation between the effective exchange rate and the terms of trade, chart 2 reports a scatter plot of the two variables.

Visually one sees, as expected, an association between the terms of trade and the effective exchange rate of sterling.

To complement visual impression, a regression was conducted between the effective exchange rate and the terms of trade for Sterling. While not giving excessive weight to the estimated coefficients, the regression indeed confirms, as one could expect, a fairly strong relationship between the terms of trade and the effective exchange rate of sterling.

Figure 2. Scatter plot and regression of the terms of trade on the effective exchange rate (REER).

Source: Eurostat and Bruegel (REER database). Note: Terms of trade are defined as the ratio between the index of export prices and the index of import prices, provided on a quarterly basis from Eurostat. The REER is calculated with respect to 41 trading partners. The REER leads 4 periods ahead.

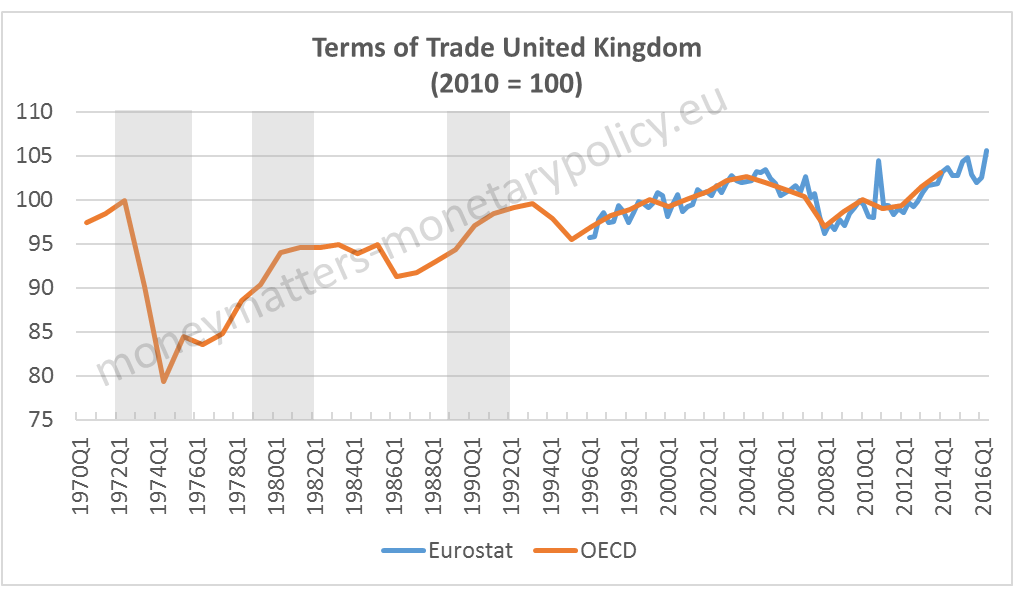

We can now compare the effect of Brexit in 2016 with the effect of the sheik-engendered oil shocks of the seventies.

Figure 3. Terms of trade of the UK.

Source: Eurostat (quarterly data) and OECD (annual data). Note: the shaded areas indicate major recessions in the United Kingdom between 1970 and 1995. In this chart, a deterioration of terms of trade is indicated by a decrease.

In the chart we see that on the occasion of the oil shock in 1973-1974 the UK terms of trade deteriorated by some 20 per cent and it took about 20 years for them to return to the 1972 level. It is interesting to recall that the oil shock was followed by a relatively long recession which forced macroeconomists to invent a new term: stagflation as, contrary to the until then prevailing experience, inflation was accompanied by stagnation. Indeed the oil shock created a dilemma situation for central banks: should they reduce interest rates to fight the recession or increase them to counter inflation?

The impoverishment brought about by Brexit is thus bigger than a half of the oil shock of 1973-74: British voters caused more than half of the damage imparted by sheiks. British voters must have voted for Brexit for a reason, but this reason is clearly not economical, as it produced an immediate loss unless, that is, it was really “stupid”, as I hypothesized.

Of course terms of trade will change going forward. If we concentrate on export and import prices, i.e. P and P*, as we have no way to foresee what the exchange rate, e, will do, we see that an improvement of the terms of trade requires P to grow relative to P*, i.e. we need inflation, as measured by export prices, to exceed the rate of growth of import prices. In short, we need domestic inflation to exceed world inflation. This is, of course, the “flation” part of the stagflation that followed the oil shock.

The process seems already under way: inflationary expectations in the UK after the Brexit referendum are reported in figure 4, showing an increased by some 50 b.p., from 3.1 to 3.6 per cent, well above the Bank of England objective.

Figure 4. Inflation expectations in the UK.

Source: Bloomberg

As domestic inflation exceeds global inflation, the terms of trade improve but the competitiveness of UK exports deteriorates. At the end, the damage from Brexit is initially an impoverishment, but an increase in competitiveness, subsequently, if the domestic rate of inflation exceeds the global one, terms of trade improve but there is a gradual loss of competitiveness. The experience after the oil shock shows that this process can last for decades.

This post was prepared with the assistance of Pia Huettl and Madalina Norocea.

- Bernanke, The Courage to Act.[↩]

- https://moneymatters-monetarypolicy.eu/where-to-place-camerons-and-johnsons-and-corbyns-recent-actions-in-carlo-m-cipollas-behavioural-chart/ [↩]

- A more sophisticated reasoning could lead to assume some effect of Brexit on P*: if companies exporting to the UK behave according to the “pricing to market” paradigm, they could take part of the sterling devaluation into their margins, i.e. they would not increase the price of their exports to the UK by the full amount of the devaluation, so lowering the price in their national currency not to increase too much the price in sterling and thus risk loosing sales. As I do not know how strong and durable this “pricing to market” could be, I do not attempt at taking it into account.[↩]