Macro-prudential: if not now when?

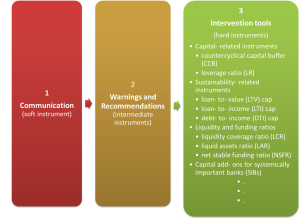

As is well known, the European Central Bank, with the support of the FED, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England, did indeed intervene, the through of the € exchange rate was surpassed and is now long forgotten, with the € some 60% stronger than it was then. This was the first time the young central bank carried out interventions in the market and it did not only contribute to a more sensible valuation of the € on the market but also made some hefty capital gains. Other, even larger, capital gains were made by the ECB in its subsequent interventions, this time on the capital market, purchasing covered bonds and peripheral sovereign bonds [2]. This is an interesting, and insufficiently considered, point, but it is not the one I want to make in this post. My own “If not now when?” refers to the opportunity to have recourse to macro-prudential measures in the €-area.There is probably more controversy about the idea of having recourse now to macro-prudential measures in the €-area than there was on intervening in the foreign exchange market when Mussa issued his “If not now when?”, but I will try and show that the case for having recourse to macro-prudential measures is a solid one.Let me start, however, recognising that macro-prudential policy is in its infancy. The problem starts with the listing of the macro-prudential tools: clearly changes in Loan to Value (LTV) ratios belong to the list together with dynamic capital charges for banks. One should probably add increased haircuts for repo operations or more generally for operations which can generate leverage (including derivative operations), but as one gets down the list, the risk of rehabilitating disgraced direct control measures under the nobler mantle of macro prudential measures increases. The chart below reports the best taxonomy of the macro prudential toolkit that I could find, elaborated by the Bundesbank.

Source: Derived from Macroprudential oversight in Germany: framework, institutions and tools, Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report, April 2013

But these difficulties are somewhat analogous to those affecting central bank interventions, both on the foreign exchange and the capital markets: their effectiveness depends so much on specific circumstances that there is no way to predict accurately whether they would indeed work or not. There are a number of circumstances that can help determine whether they would be useful or not, but there remains a lot of uncertainty.

The uncertainty about the definition, calibration and effects of macro prudential measures feeds an unsettled controversy among economists. If the central bank has only one tool, interest rates, and two objectives, price and financial stability, dilemma situations may arise in which one objective would require an increase (or a decrease) of interest rates while the other objective would require the opposite. Those who have more trust in the usefulness of macro-prudential measures stress that they can solve the monetary policy dilemma, as they allow respecting the famous Tinbergen rule that there should be at least as many tools as there are objectives. Those who are more sceptical about the effectiveness of macro-prudential tools stress that interest rates reach all parts of the economy while macro-prudential measures risk affecting only the banking sector or, at most, the formal component of the financial sector, giving incentives for the development of the “shadow banking system”.

All the uncertainties and doubts are justified, it is however my sense that now is the time to start experimenting with macroeconomic tools in the €-area. And I do not seem to be alone with this idea. President Draghi, somewhat surprisingly, recently said that one of the three challenges facing the ECB, in addition to the obvious ones of fighting too low inflation and establishing the Single Supervision Mechanism, is: “…, macro-prudential policy can be used to address financial stability concerns and facilitate our monetary policy conduct. …, where the financial stability concerns are of a systemic nature affecting the whole euro area, those policies will have to be coordinated. …[where], national macro-prudential authorities may take actions to reduce the risk of local financial imbalances.” [3]

[4] Jens Weidmann, Crisis economics – the crisis as a challenge for economists, Lecture at the Annual Gala Meeting of the Munich Volkswirte Alumni-Club,June 2013