Libra versus TIPS

This is an extended version of the post published on the Bruegel Website on January 27: https://bruegel.org/2020/01/libra-as-a-currency-board-are-the-risks-too-great/

Introduction

The Libra project,1 about which new information is slowly trickling down,2 has received a barrage of criticisms from authorities3. In the face of regulatory uncertainty, seven of its 28 high-profile funding members left the project in less than a month—including Paypal, Mercado Pago, Mastercard, VISA, Stripe, and eBay. It is now not clear that the project will be launched, at least in the shape under which it was initially proposed4. But whatever the outcome, Libra is certain to provide for heated discussions around so-called stable coins and the future of money more generally5.

Critics of Libra have largely focused on risks for:

- Money laundering, terrorist financing, and tax evasion;

- Financial stability (e.g. facilitating bank runs), including foreign exchange stability;

- Data privacy;

- “Crowding-out” of unstable currencies in emerging economies;

- Monetary sovereignty (i.e. control over monetary policy tools); and

- Market concentration.

This paper looks at another specific issue of the project: that of monetary management. Libra is presented by its promoters as a payment system innovation:

“Just as people can use their phones to message friends anywhere in the world today, with Libra, the same can be done with money — instantly, securely, and at low cost.”6

Yet, as we argue here, Libra is not just a payment system but rather a new monetary system (section II). The project is indeed presented in a sufficiently ambiguous fashion to be also assimilated to a currency board by its proponents. But the problems of monetary management that a currency board arrangement raises are completely overlooked by its proponents. Destabilising shocks threaten all monetary systems, including a simplified monetary system like a currency board, and Libra is no exception (section III). To ensure their stability, successful currency boards such as Hong Kong’s resort to active management and discretionary interventions—a fact that is glossed over by Libra proponents (section IV). This omission is understandable, given that no institution with a monetary expertise could be found among the sponsors, but no less serious for that (section V).

We also argue in this paper that the payment system progress promised by Libra could potentially be achieved without the need for building a new monetary system (section VI). Indeed, it could be achieved, admittedly with quite some extensive work, by expanding existing systems which enable payment service providers to offer fund transfers to their customers in real time, 24/7, such as the ECB’s recently implemented TIPS7 (other similar systems include the EBA Clearing RT1 and the upcoming FED’s FedNowSM Service).

Why is Libra best characterised as a new monetary system?

As set-out in the project’s White Paper, the Libra initiative is characterised by the following three attributes:

- Decentralised (blockchain) technology;

- Private centralised issuer (the Libra Association); and

- Value fully backed by highly liquid, high-quality assets.

Each Libra coin represents a claim on the Libra reserves to be held in the form of a basket of bank deposits and short-term government securities. As such, Libra coins could be seen, in a first interpretation, as a specific class of stablecoins called “tokenised” or “fiat-backed” stablecoins8. This arrangement implies a commitment to full redeemability9.

But, while Libra is presented asa a tokenised stablecoin for a new payment system, in a second, more convincing interpretation, it is rather a new currency for a new monetary system. Indeed, the strategy adopted by the Libra Association seems to exclude the pure tokenisation of an existing currency. This may look controversial, but it’s very proponents refer to a monetary system, specifically at a currency board10:

“As discussed earlier, the mechanics of interfacing with our reserve make our approach very similar to the way in which currency boards (e.g., of Hong Kong) have operated.”11

The Libra initiative is indeed akin to a blockchain-powered currency board regime. Currency boards are a specific variant of a general class of monetary systems in which the outstanding amount of the items on the asset side of the issuing entity (a monetary authority or a private issuer) is exogenous to its action. Under a currency board, the issuer holds, on its asset side, currency created by another central bank (U.S. dollars, for instance, in the case of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority). Similarly, Libra would hold high quality and liquid assets, such as bank deposits and government securities from stable and reputable issuers. This feature distinguishes Libra and currency boards from fiat currency systems, in which the central bank can create money against assets that it itself generates—e.g., the ECB or the FED can create money in their monetary policy operations against credit extended to commercial banks.

Analogously to a currency board central bank, a narrow commercial bank could not issue new loans as the corresponding asset for new deposits (as it is described for instance in the money multiplier process): it must keep its deposits just equal to its reserves held with the central bank (i.e. narrow banks are a 100% reserve banks). This characteristic also extends to the gold standard, and metallic systems more generally12. Under the gold standard, the exogenous asset is produced by mines and, in the most extreme form of the system, the central bank can issue currency only if it acquires more of the exogenously determined stock of gold.

Unlike a traditional monetary system, however, the Libra issuer is a private association, not a legally-mandated monetary authority13. Whereas a traditional currency board is run by sovereigns following a legally-binding stability mandate (monetary and financial), Libra is a profit-making enterprise. This difference has important implications for the stability of the Libra currency, as we show later in this paper. Libra proponents fail to explore the implications of such a critical difference.

Those convinced by Hayek that the solution to a stable currency lies in competing monies issued by private banks, may think that the Libra approach is a step in the right direction14. Indeed, there are similarities between Libra and Hayek’s private Swiss Ducat, but these are less important than the differences.

The most important similarity is that Libra would be a privately issued currency, like the Ducat. However, Libra would hold fiat currencies in its reserves. This is in flat contradiction with Hayek’s idea that the Ducat should be completely detached from—and indeed antagonistic to—fiat currencies.

According to the first interpretation presented in section II, the taxonomy proposed by Bullman, Klemm and Pinna (2019, henceforth “BKP”) would put Libra in the category of tokenised (i.e. fiat-backed) funds. Under the same taxonomy, Hayek’s Ducat falls under “algorithmic” stablecoin, “backed by users’ expectations about the future purchasing power of their holdings, which does not need the custody of any underlying asset, and whose operation is totally decentralised.” The two stablecoin variants thus lie at the two extremes of the novelty and stability ranges proposed by BKP: tokenised funds are the least innovative and most stable variant, net of any actual or perceived misbehaviour by the issuer, while algorithmic stablecoins is the most innovative and least stable one15.

Another possible difference between Libra and the Ducat is that, for Hayek, free competition between issuers of different monies is critical. The network externality advantage of a tech behemoth like Facebook, with its billions of users, does not quite convey a message of competition. One cannot exclude, however, that another internet giant, like Amazon or Google, could emerge as an effective competitor, leading to oligopoly. The probability of seeing free competition emerging looks dim.

Exploring Libra’s potential for developing into a Ducat-like currency, however, far exceeds the ambitions of this paper. Leaving this fascinating question aside, we focus on the internal mechanics of Libra and argue that Libra proponents seem to have succumbed to the attraction of the illusory simplicity of a tokenised stablecoin instead of addressing the complications of a currency board system. Let us now develop this point.

Libra, like a currency board, the gold standard or a 100% reserve banking system would require management

In Libra, currency boards, gold standard central banks or 100% reserve banks, the issuing entity holds different items on the two sides of its balance sheet and must continuously keep consistency between the two. Figure 1 below presents a simple T account, assuming that the counterparts of issued Libra are commercial bank deposits (held in proportion α) and government bonds (held in proportion 1-α). See Appendix 2 for a detailed flow of funds account.

Figure 1. Flow of funds account representation of Libra issuer

| Libra issuer | |||

| Deposits with bank | α(Libra) | Libra issued | Libra |

| Gov. bonds | (1-α)(Libra) | ||

Shocks (supply or demand) will inevitably hit both asset and liability sides of the Libra issuer’s balance sheet. Such shocks will have destabilising effects (i.e. creating an inconsistency between the Libra currency on the liability side and exogenous assets on the asset side), unless one of the following two restrictive assumptions hold.

Shocks to Libra would not have a destabilising effect if the issuer would allow shocks to fully affect the value of its liabilities, i.e. if it would let its currency freely float. But letting the currency freely float would contradict Libra’s stated aim of stability, where ‘stability’ is explicitly meant in terms of purchasing power towards real goods: a cup of coffee in Libra’s presentation. Indeed, Libra is “designed to be a currency where any user will know that the value of Libra today will be close to its value tomorrow and in the future”.

Shocks affecting the two sides of the balance sheet would also not have a destabilising effect if theyare always small or, if large, very closely correlated. Full redeemability of Libra might suggest that, as long as the Libra issuer can accommodate any request for issuance and redemption and it can maintain public confidence that the assets in its reserves are not stolen or misused, then the second condition would be fulfilled and the two sides will remain balanced16.But these are the conditions that would prevail only if Libra could be confidently be expected to behave like a tokenised stablecoin. Looking at financial history however, it appears very imprudent to base the entire construction on this unwarranted assumption. In fact, experience with currency boards (and metallic systems) shows that the maintenance of a peg of a currency toward reserve assets requires very active protection for the maintenance of public confidence.

On the liability side, in particular, changing expectations can generate important destabilising shocks. In national currency boards, conflicting commitments on the part of the government may drive fears that it abandons its monetary commitment in order to pursue some macroeconomic goal, e.g. abandoning the peg to reduce the damage from an economic collapse (the representative case of Argentina is discussed in the next section).

In private currency boards, the profit motive plays the role that macroeconomic interests play in national currency boards. Libra holders may fear that, in the face of profit opportunities, the Libra Association ends up violating its commitments, e.g. that it issues more liabilities than granted by its assets, that it suspends convertibility or, even more extremely, that it debases Libra. Such cases have ample historical precedent, for instance in metallic systems.

One Libra-specific vulnerability lies in its recognised right to change the reserves’ composition. Such changes would, according to the project, be exceptional and subject to strict decision-making. This feature, however, may determine speculative activities: in particular if Libra holders expect a composition change which could imply a jump in the value on the asset side of the balance sheet, speculation could drive demand for Libra up or down for fairly long periods.

The very low yield that could be earned, now and in the foreseeable future, from holding highly liquid and high-quality reserves (as further discussed in section V), may drive deviations from Libra’s commitment to stability. Indeed, holders may fear that Libra succumbs to the “chasing for yield syndrome” that is affecting a number of financial institutions. In particular, Libra holders may fear that Libra is tempted to change the composition of reserves in order to enhance the meagre return on its assets—i.e. giving more weight to less liquid and less creditworthy, but higher-returning, assets17.

The temptation to look for yield may be aggravated by two other distinctive features of Libra.

First, interest on the reserves will be used, among other things, to pay dividends to the currency’s first investors18. These first investors, however, also happen to be Libra board members who may see their financial interests conflicting with the stability of the system. The incentive structure of Libra is thus inimical to the currency’s stability.

Second, and compounding the incentive issue, Libra Association members will be subject to limited liability19.Limited liability undermines the credibility of the Association in satisfying the claims of Libra holders in full faith and credit, as central banks do with public money. In the absence of a deposit guarantee scheme, any doubts in the association’s commitment to the fixed exchange rate and/or full redeemability will be severely punished by currency holders. In fact, to the extent that the initiative lacks proper governance and clear regulation, Libra is likely be more susceptible to destabilising flows than any traditional currency board system.

On the asset side, shocks should normally be less severe, but their occurrence will depend on whether, as originally announced, the reserves are invested in a basket of currency (somewhat inspired by the SDR) or whether they are invested into a single currency (inevitably the dollar). The exchange rate shocks in the second case will be larger, since there will be no portfolio effect to help attenuate them. In this respect it can be recalled that in 2014-2015, the exchange rate between the US dollar and the SDR fluctuated by up to 14%20.

As we have seen in this section, asymmetric shocks threaten the stability of currency boards. Libra, is no exception. Yet some currency board systems, such as Hong Kong’s, have proved resilient. To ensure stability, successful currency boards systems foresee stabilising mechanisms in their construction. These amount to: (i) an organizational set-up that allows for interventions, also on a discretionary basis, lest shocks unduly affect the value of the currency, and (ii) operational tools to implement such decisions. One solution for Libra may be to adopt its own stabilising mechanisms. But are they within reach of the initiative? In the next sections, we explore historical examples of currency boards and draw lessons for the Libra project.

Currency boards, gold standard and narrow banks.

In this section, we look at actual examples of currency boards as well as, very briefly, at the gold standard and the “narrow banks” proposals.

Appendix 1 lists the cases of modern currency board we could find, with their start and end date as well as an assessment of whether they ended or not with a forced exit. The cases can be mostly classified in three categories:

- Very small countries, e.g. Djibouti, Bosnia-Herzegovina or the islands participating to the East Caribbean Central Bank.

- Temporary arrangements, e.g. two Baltic countries in which the currency board was a bridge to the adoption of the euro.

- Permanent currency boards for countries of non-negligible size, e.g. Hong Kong and Argentina.

Permanent currency boards are the most relevant category for assessing Libra, since Libra is neither a temporary arrangement nor is it supposed to have very small scale. We thus examine the cases of Hong Kong and Argentina in more detail in order to draw lessons for the Libra project.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s currency board, introduced in 1983, has proved very resilient. This success most certainly drives Libra’s desire to explicitly compare itself with the territory’s monetary system. What the paper does not discuss, however, is that Hong Kong’s success rides on a complex framework with demanding features. We will discuss the following three demanding features in turn: (i) greater than 100% reserve, (ii) high transparency and public outreach, and (iii) active monetary management.

First, the HKMA maintains a greater than 100% reserve21. The equity buffer represents an insurance for the HKMA’s ability to defend the currency peg, enhancing the system’s credibility.

Second, the HKMA abides by high transparency standards and commits to public outreach and education. Market operations conducted by the HKMA are announced immediately, and relevant data are published daily. Prior to any major reform in the system, senior HKMA officials inform market participants about the changes, and research papers are published to provide background information and explain the rationale behind the changes. Furthermore, the HKMA releases the minutes of the meetings of the Currency Board Governing Committee, and Currency Board accounts data and other relevant statistics are published every month.

Third, and most important, the success of Hong Kong’s currency board depends on active management—which includes mechanical as well as discretionary interventions in the currency and money markets. Indeed, while interventions in the currency market are largely mechanical since May 200522, the HKMA does retain and exercise some discretion.

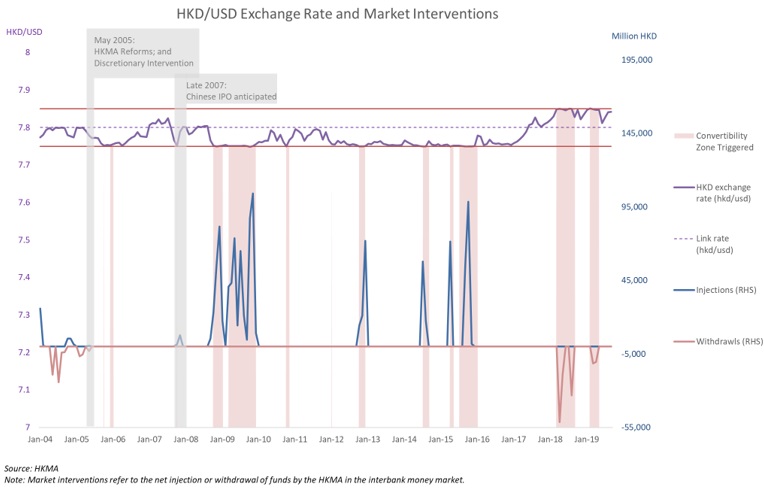

Let us first examine the mechanical stabiliser. When capital inflows (or outflows) push the exchange rate outside the narrowly defined range around the central parity (the “Convertibility Zone”)23, the HKMA automatically intervenes to sell (or buy) the HKD against the USD (see Figure 1). These interventions cause the monetary base to expand (or contract), putting downward (or upward) pressure on interbank interest rates, which in turn counteract the original capital flows and ensure that the exchange rate remains stable. In other words, interest rates offset, at least partially, the effects on exchange rates of capital inflows and outflows in Hong Kong.

Figure 2. Hong Kong dollar exchange rate and spread to US interest rate. (2004-2019)

As stated above, the HKMA is not limited to mechanical interventions. Indeed, it retains and exercises some discretion, i.e. it can also act within the convertibility zone. The HKMA has used its discretionary powers at least three times since the May 2005 reform, as indicated by the vertical bars in the figure.

The first discretionary intervention occurred only seven days after the reform24. To address rising demands for the HKD ahead of a number of large IPOs, the HKMA conducted a market intervention within the Convertibility Zone (selling HKD 544 million to banks, see figure 2 below)25. The operation was effective in limiting the sharp increase in overnight HKD interest rates throughout the subscription periods of the IPOs.

Figure 3. Interventions of the HKMA: Injections and withdrawals of Hong Kong dollars against US dollars. (2004-2019)

In its second discretionary intervention, in late 2007, the HKMA injected liquidity within the Convertibility Zone—again in anticipation of increased demand for the HKD ahead of large-scale IPOs. Note that in the following months, and in the wake of the US subprime crisis, no further discretionary market interventions were conducted: mechanical interventions were effective in anchoring the exchange rate and maintaining a stable interest rate differential with the US (see figures 1 and 2 above)26.

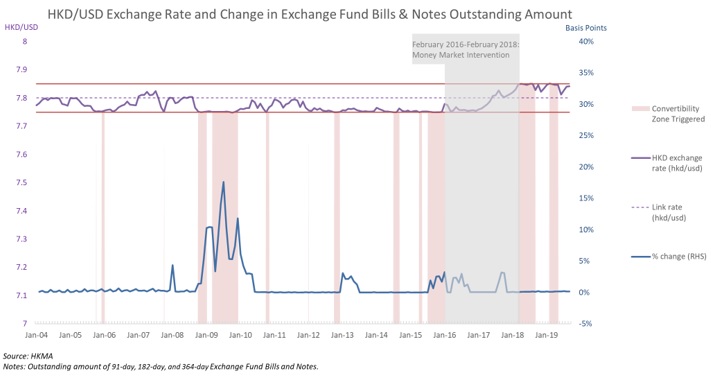

Furthermore, the HKMA intervenes intermittently in the money markets to stabilise interest rate differentials with the US. The interventions rein in differentials by selling exchange fund (EF) bills and notes, thus soaking up excess cash27. Starting in 2015, following the Federal Reserve’s interest rate increases from ultra-low, post-2008 levels, the gap started to widen. Higher US interest rates drew money to the higher-yielding US instruments, causing investors to sell HKD for USD. In the two-year period leading up to February 2018, the gap widened to 100 basis points, without, however, the exchange rate veering outside of the Convertibility Zone a single time (automatic market intervention was not triggered until March 2018). While the HKMA did not intervene by buying currency, it did step in by selling EF bills and notes, whose outstanding balance increased by 23% over the two-year period (see figure 3 below).

Figure 4. Interventions of the HKMA: Selling of Exchange Fund Bills and Notes. (2004-2019)

The case of Hong Kong shows that a complex framework with demanding features, including active management, is needed to maintain consistency between the national currency on the liability side and a foreign currency on the asset side, and to insure stability in the face of potentially offsetting flows. Can the Libra association adopt the tools used in Hong Kong to guarantee the stability of its currency? In section V, we discuss Libra’s limitations in mirroring the Hong Kong example.

Argentina

The case of Argentina is a dramatic one. But the Argentinian regime, initiated in 1991, is not a textbook example of a failed currency board, and so we will not discuss it in detail here28, especially since Libra specifically draws from the Hong Kong success and does not mention the Argentinian failure.

We do note, however, that the Argentinian case demonstrates the limits of commitments in stabilising expectations about a currency board’s credibility—even when these commitments are enshrined in law. In 2001, in the face of a four-year recession and a massive budget deficit, devaluation concerns started to mount. Changing expectation drove large capital outflows and interest rates rose to up to 60%, escalading the government’s budget deficit. Under intense pressure, the peg was formally abandoned in 2002.

The Argentinian case also undermines the common belief that currency boards can buy credibility by increasing the cost of abandoning the peg29. The Argentinian board had set very high costs for itself, yet expectations failed to stabilize. The Argentinian authorities could not credibly maintain both fiscal and monetary commitments. Monetary commitments were ultimately abandoned, and high costs incurred.

The Argentinian case is an occasion to ask: to what extent might we expect a profit-driven currency board regime—with no legally-binding public mandate—to maintain its commitments in the face of shocks? We explore this question further in section V.

The Gold Standard and Narrow Banking

As mentioned above, another monetary system analogous to Libra is the gold standard, whose experience is both too complex and too well known to be illustrated here.

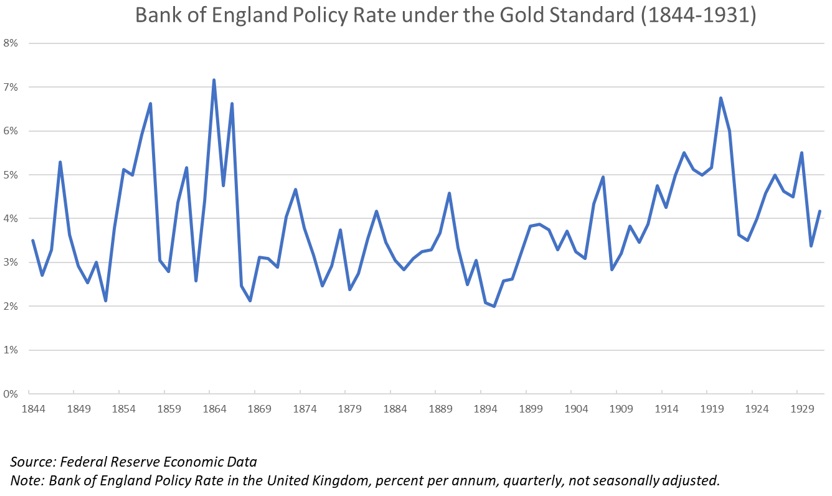

It suffices to recall that such a system was definitely abandoned, and for good reasons. After the huge economic losses of the thirties, there is really no prospect of reinstating it. The gold standard required difficult management in terms of interest rates. Figure 3 below illustrates this point through the case of the Bank of England, which had to actively manage its interest rate to maintain the gold parity, reaching peaks well above 6 per cent. Further possible tools to manage the gold standard were the “fiduciary issue”, i.e. the possibility to issue in excess of the gold coverage, for a limited amount, as well as the temporary suspension of convertibility30. The gold standard, and metallic system in general, were even prone to the less commendable activity of debasing the currency, i.e. secretly reducing its precious metal content.

Figure 5. Bank of England Policy Rate under the Gold Standard. (1844-1931)

Another close relative of currency boards, i.e. 100% reserve banking (aka narrow banking), has never been tried in practice. This is notwithstanding illustrious academic support: Irving Fisher and Henry Simons were strong proponents of the so-called Chicago Plan of 193331. In Switzerland, an attempt to introduce a variant of 100% reserve banking (under the name of “Vollgeld”) was rejected by 76 per cent of Swiss voters in a referendum in 2018, following the strong advice given by the Swiss National Bank. Another attempt to implement the principle of 100 % reserve banking is ongoing in the US32, where a narrow bank was proposed to arbitrage the difference between the higher interest rate offered by the Federal Reserve on bank reserves and the lower interest rate that non-banks can obtain on the money market or on so-called reverse repos with the Fed.

Lessons for the Libra project

The key take-away for Libra is that active management is a necessary condition for stability, unless the initiative is somehow spared the shocks that hit all other similar monetary systems. But, as discussed in section III, there is no reason to believe that Libra wouldn’t fall prey to destabilising shocks. While Libra is not subject to speculation around conflicting national interests (e.g. monetary versus fiscal), it may be subject to speculation around its profit-driven interests, e.g. fears that Libra would trade financial profit for stability.

Our result so far is that Libra needs active management. However, the project’s description fails to adequately address this need, only stating that “the mechanics of interfacing with our reserve make our approach very similar to the way in which currency boards (e.g., of Hong Kong) have operated.” This omission is convenient: in the absence of a clear governance structure, the Libra board would not be equipped for active management.

As mentioned above, one of the major difficulties for managing Libra (or currency boards, a re-exhumated gold standards or a 100% reserve banking) lies in maintaining consistency between the issued currency on the liability side and the exogenous asset on the asset side in the face of shocks. Particularly difficult is the possible disruptive effect of expectations. When the market has doubts about the maintenance of the dollar peg of the Hong Kong currency, in either direction, the central bank intervenes to reassure the market (i.e. indirectly adjusting interest rates and carrying out quantitative interventions).

In the case of Libra, no entity is given the clear responsibility to respond to shocks (such as those generated by changes in expectations). Who will stand ready to defend Libra in the event of a crisis?

But even if a given entity was attributed responsibility for managing Libra, this hypothetical entity would lack the tools necessary to discharge this task. In the rest of this section, we discuss four missing tools: (i) equity buffers, (ii) interest rates, (iii) transparency and proactive communication and education, and (iv) a legal mandate.

First, it is difficult to foresee how Libra will accumulate the equity necessary to intervene and offset potential imbalances between its assets and its liabilities (i.e. accumulate a greater than 100% reserve). Libra is supposed to invest into liquid and high credit securities. But these are exactly the securities that have very low and even negative yields now and, looking at forward rates, in the future. For instance, a composite security made up of GDP weighted US, German, French, Japanese and UK Treasury bills would have a yield of 0.88 per cent33—hardly encouraging to accumulate a protective buffer34. The hope, mentioned in the Libra project, to be able to give “grants to nonprofit and multilateral organizations, engineering research, etc.” seems somewhat pie in the sky. Most probably Libra will have problems making its books break even.

Second, the Libra board will miss interest rates as an important stabilising tool. Indeed, as discussed above in the context of Hong Kong, interest rates are an important tool in offsetting the effects of capital inflows and outflows. HKMA interventions work by affecting the demand for (or supply of) the HKD through interest rates. Libra on the other hand is stuck with a 0% rate so that its board is quite simply unequipped to similarly affect the demand for (or supply of) its currency to counter destabilising flows.

Third, stable expectations in currency boards are built on transparency and proactive communication and education. The extent to which we can expect a profit-driven enterprise to meet the standards of a legally-mandated public institution is very much an open question.

Finally, in the absence of a legal mandate, it is not clear that the stabilisation tools just discussed would achieve their intended efficacy in the hands of the Libra Association. Indeed, these tools can potentially stabilise expectations. But in the face of enticing profit opportunities (or life-threatening losses), might holders not rightly question the association’s binding commitment to use the stabilising tools?

Regulation might work to overcome some of the challenges discussed in this section, e.g. mandating an equity buffer. However, regulating a global currency such as Libra will require deep cross-border coordination and a genuine acceptance to be regulated. Another pie in the sky?

Innovations in payments systems, without the need to concoct a new monetary system, can bring about the advantages that Libra is supposed to deliver

If the objective is, as recalled above, to come to a situation in which “Just as people can use their phones to message friends anywhere in the world today, with Libra, the same can be done with money — instantly, securely, and at low cost” then working on existing instant payment systems seems a more promising avenue. This will be illustrated with the ECB TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (“TIPS”), but other instant payment systems, such as EBA RT1 or the future FedNow Service would offer similar opportunities.

TIPS was implemented by the ECB in November 2018 and enables citizens and firms to transfer, via a bank intermediary, money in real time, 24/7 and 365 days a year. TIPS payments are settled on the books of the Eurosystem in central bank money and cost 0.20 euro cents for the first two years35.

TIPS falls short of delivering on Libra’s ambitions for two reasons:

- TIPS lacks the global reach promised by Libra, since it is only available for payments in euro in the euro area (at least for the time being); and

- TIPS lacks the scale envisioned by Libra since it requires bank intermediation36.

The first limitation could be obviated by central bank collaboration. Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, has proposed that central banks collaborate to issue a digital currency that would substitute the dollar as the dominant international currency. However, a much lower level of collaboration would suffice to make the different instant payment systems developed by central banks connect in a network. In fact, TIPS is open to any national central bank that wishes to make its currency available for central bank money settlement in TIPS. The Deputy Governor of Sveriges Riksbank, Cecilia Skingsley, announced at a conference37 that the Swedish central bank is looking into adopting TIPS.

The next step in expanding TIPS globally would require achieving currency conversion, i.e. surpassing the current requirement that all accounts involved in a transaction be denominated in the same currency. This is a big step, but not one that looks insurmountable: one could imagine that either the sending, intermediating or receiving bank in TIPS, or another interlinked instant payment system, could perform the currency conversion according to an agreed framework. This development was indeed considered desirable by Skingsley. Continuously Linked Settlement Bank (“CLS”), which assures payment after payment settlement of foreign exchange deals, could possibly be developed to help with such an endeavor.

The second limitation is potentially more difficult to surpass. TIPS requires traditionalbank intermediation, which limits its ability to reach the scale envisioned by Libra for two reasons. First, it is very difficult to reach non-banked people and no bank, or consortium of banks, seems in the position to reach the billions of customers that Facebook, which is behind the Libra project, can reach through its authorised resellers. Second, bank participation in TIPS has been limited so far. Indeed, substantial participation can only come if banks are incentivised (perhaps as a result of competitive pressures) to offer this superior payment system to their customers.

These look like serious issues, but they are of a much lower order of magnitude than would be creating and managing a new monetary system like Libra.

Maybe Libra could even help in dealing with these two problems, by letting its non-banked users access the instant, multi-currency payments services offered by central banks rather than going the full distance of creating a new monetary system. This would require, however, Libra becoming a bank in a number of jurisdictions—though perhaps one that is limited to only offering payment services.

Central Bank Digital Currency (“CBDC”) may offer another alternative to Libra—i.e. a digital payment system that debits and credits accounts directly held by individuals with the central bank. Two issues would have to be appropriately considered, however. First, and most importantly, a CBDC has its disadvantages, in particular in terms of potential bank disintermediation, and it is not as yet clear that a CBDC would provide net benefits. Such a radical step to improve the payment system could be taken only if the negative impacts of CBDC issuance could be avoided and the costs of its implementation were not too high. Second, one would have to consider whether the non-banked are more likely to access a central bank than a bank.

Conclusion

Libra is a slippery project, known to change shape in pace with its critics. If criticised on the payment front, it’s a currency. If questioned on the monetary front, it’s a payment system. The final shape of Libra is yet unclear. But despite the ambiguity, Libra provides a useful test-case for thinking about (tokenised) stablecoin initiatives. More generally, Libra has and will continue to fuel debates around the future of money—as well as reviving old debates around private versus public money38.

Examining Libra as a currency board, we conclude that creating a new monetary system is a disproportionate and potentially ineffective approach for achieving a safe, stable, cheap, simple, and instantaneous global payment system. Working on central banks instant payments looks like a more promising avenue, though progress may be slow and will require a lot of ingenuity and work on the part of central banks as well as commercial banks.

Appendix 1

Modern currency boards39

| Country | Start year | End year | Forced exit? | Peg currency | Backing rule | Actual backing | Reserve assets |

| Argentina | 1991 | 2002 | Yes | USD | 100% of monetary base | 139% of M0, 23% of M2 | Foreign assets, gold, USD government bonds |

| East Caribbean Central Bank countries (ECCB)40 | 1965 | On-going | n/a | USD | At least 60% of demand liabilities | above 90% since the

early 2000s |

Foreign assets and gold |

| Brunei | 1967 | On-going | n/a | Singapore dollar | At least 70% of demand liabilities (of which 30% in liquid assets) | 80% of CB’s demand liabilities | Liquid foreign assets, foreign securities, accrued interests |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 1997 | On-going | n/a | DMark/ euro |

100% of monetary liabilities of CB | 110% | DM/euro-denominated assets |

| Bulgaria | 1997 | On-going | n/a | DMark /euro | 100% of CB liabilities | 148% of M0, 54% of M2 | Foreign assets and gold |

| Djibouti | 1949 | On-going | n/a | USD | 100% of currency | 113% of M0, 22% of M2 | Foreign assets |

| Estonia | 1992 | 2011 | No; adopted euro | DMark /euro | 100% of M0 (excluding CB certificates) | 122% of M0, 47% of M2 | Foreign assets and gold |

| Hong Kong | 1983 | On-going | n/a | USD | 100% of “certificates of Indebtedness” issued to note-issuing banks | 110% of M0 | Foreign assets |

| Lithuania | 1994 | 2015 | No; adopted euro | USD | 100% of currency and CB liquid liabilities | 112% of M0, 51% of M2 | Foreign assets and gold |

Sources: Ghosh et al (2000); Myrvoda et all (2018)

Appendix 2

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate, under two different configurations, how Libra funds may flow, as drawn by Bindseil (2019)41. The balance sheet items prevailing before the issuance of Libra are presented in black. The changes brought by the introduction of Libra are in red and green.

Figure 1 represents Libra issuance where counterparts are commercial banks’ deposits and government bonds (consistent with the project’s description). In this case, the Libra issuer holds on its asset side both bank deposits (in proportion ) and corporate/government bonds (in proportion 1-a). Figure 2 represents Libra issuance where counterparts are central bank deposits (aka reserves). In this case, the Libra system mirrors a narrow bank (see below).

In both cases, we assume that a portion of commercial banknotes (Libra1) and bank deposits (Libra2) held by households and non-bank corporations are substituted with Libra currency42. Note that the ratio between Libra1 and Libra2 determines the relative disintermediation of banks and the central bank: the higher is Libra2 with respect to Libra1, the higher the degree to which commercial banks are disintermediated with respect to the central bank.

Figure 1: Financial accounts representation of Libra issuance with commercial banks deposits and government bonds as counterparts.

| Households, pension and investment funds, insurance companies | |||

| Real Assets | 20 | Household Equity | 40 |

| Sight deposits | 5 – Libra2 | Bank loans | 5 |

| Savings + time deposits | 4 | ||

| LIBRA | Libra2 + Libra1 | ||

| Banknotes | 1 – Libra1 | ||

| Bank bonds | 4 | ||

| Corp./Gov. bonds | 7 | ||

| Equity | 8 | ||

| Libra issuer | |||

| Deposits with bank | α(Libra2+Libra1) | LIBRA issued | Libra2+Libra1 |

| Gov. bonds | (1-α)(Libra2+Libra1) | ||

| Commercial Banks | |||

| Loans to corp. | 8 | Sight deposits | 7-Libra2 |

| Loans to gov. | 2 | LIBRA Deposits | α(Libra2 + Libra1) |

| Loans to HH | 5 | Savings + time deposits | 5 |

| Corp/Gov bonds | 5 – (1 – α)(Libra2 + Libra1) | Bonds issued | 4 |

| Central bank deposits | 0 | Equity | 3 |

| Central bank credit | 1 – Libra1 | ||

| Central Bank | |||

| Credit to banks | 1 – Libra1 | Banknotes issued | 1 – Libra1 |

Figure 2: Financial accounts representation of Libra issuance with reserves with the central bank as counterparts.

| Households, pension and investment funds, insurance companies | |||

| Real Assets | 20 | Household Equity | 0 |

| Sight deposits | 5-Libra2 | Bank loans | 5 |

| Savings + time deposits | 4 | ||

| LIBRA | Libra1+Libra2 | ||

| Banknotes | 1-Libra1 | ||

| Bank bonds | 4 | ||

| Corp/Gov bonds | 7 | ||

| Equity | 8 | ||

| Libra issuer | |||

| Deposits with CB | Libra1+Libra2 | Libra issued | Libra1+Libra2 |

| Commercial Banks | |||

| Loans to corp | 8 | Sight deposits | 7-Libra2 |

| Loans to gov | 2 | Savings + time deposits | 5 |

| Loans to HH | 5 | Bonds issued | 4 |

| Corp/Gov bonds | 5 | Equity | 3 |

| Central bank credit | Libra2 | ||

| Central Bank | |||

| Credit to banks | 1+Libra2 | Banknotes issued | 1-Libra1 |

| Deposit of banks | 0 | ||

| Libra Deposits | Libra1+Libra2 | ||

References

- Bindseil, Ulrich. “Some pre-1800 French and German central bank charters and regulations.” Available at SSRN 3177810 (2019a).

- Bindseil, Ulrich. “Central Bank Digital Currency: Financial System Implications and Control.” International Journal of Political Economy 48.4 (2019): 303-335.

- Bullmann, Dirk, Jonas Klemm, and Andrea Pinna. “In search for stability in crypto-assets: Are stablecoins the solution?.” ECB Occasional Paper 230 (2019).

- Ghosh, Atish R., Anne-Marie Gulde, and Holger C. Wolf. “Currency boards: more than a quick fix?.” Economic Policy 15.31 (2000): 270-335.

- Myrvoda, Ms Alla, and Julien Reynaud. Monetary Policy Transmission in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union. International Monetary Fund, 2018.

- Von Hayek, Friedrich A. Denationalisation of money: The argument refined. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2009.

- For an overview of the Libra project read Demertzis and Mazza, Libra: possible risks in Facebook’s pursuit of a ‘stablecoin’ (https://bruegel.org/2019/07/libra-possible-risks-in-facebooks-pursuit-of-a-stablecoin).[↩]

- B. Eichengreen, Libra: The known unknowns and unknown unknowns. VOX Ceps Policy Portal. 28 August 2019 (https://voxeu.org/article/libra-known-unknowns-and-unknown-unknowns).[↩]

- See for instance the G7 report on the impact of global stablecoins (https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d187.pdf) or the BIS 2019 Annual Economic Report (https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2019e3.htm).[↩]

- Recent statements suggest Libra may not be based on a basket of stable currencies but on an individual currency instead. (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-imf-worldbank-facebook/facebook-open-to-currency-pegged-stablecoins-for-libra-project-idUSKBN1WZ0NX).[↩]

- See, for instance, ECB’s Benoit Coeure September 2019 speech: “All things considered, Libra has undoubtedly been a wakeup call for central banks and policymakers.” See also Grégory Claeys, Maria Demertzis “The next generation of digital currencies: in search of stability” (https://bruegel.org/2019/12/the-next-generation-of-digital-currencies-in-search-of-stability/)(https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2019/html/ecb.sp190925~3afa2f7508.en.html).[↩]

- See the White Paper that launched the Libra project (https://libra.org/en-US/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2019/06/LibraWhitePaper_en_US-1.pdf).[↩]

- https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/target/tips/html/index.en.html[↩]

- In the taxonomy proposed by Dirk Bullmann, Jonas Klemm, Andrea Pinna. In search for stability in crypto-assets: are stablecoins the solution? ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 230. August 2019[↩]

- With, however, two caveats (thanking Andrea Pinna for pointing them out). First, redeemability can only be exercised by ‘authorised resellers’, not end users. As envisaged in the Libra White Paper, authorised resellers are the only entities authorised to transact in large volumes in and out of the reserve. Second redeemability means getting a share of the reserves held by the Association, not the value Libra coins were initially issued against. So, for instance, if the value of the reserve falls, the authorised reseller that redeems a holding equal to 1% of the overall Libra in circulation is going to receive 1% of the Libra reserves held as assets, which can have a far lower value than what the authorised reseller paid initially to purchase Libra units[↩]

- See also Fatás et al. (https://voxeu.org/article/benefits-global-digital-currency).[↩]

- Emphasis is ours. https://libra.org/en-US/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2019/07/TheLibraReserve_en_US_Rev0723.pdf[↩]

- Before 1800 these were mostly based on silver, see U. Bindseil (2019a).[↩]

- See SAFE paper for a more detailed discussion of the distinction between Libra and traditional currency boards (https://safe-frankfurt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/editor_common/Policy_Center/SAFE_Policy_Letter_No_76.pdf).[↩]

- F. A Hayek: Denationalisation of Money, The Argument Refined: An Analysis of the Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies. Institute of Economic Affairs Publication. Third Edition 1990.[↩]

- Note, however, that while Hayek would just close down central banks, an algorithmic stablecoin would be issued by an algorithmic central bank, that just implements a monetary rule fixed once and for all. Also Hayek proposes a rule for the private issuer of Ducat: change, if needed with high frequency, the quantity of money issued to keep its value constant with respect to an index of raw material prices. For those familiar with the complications of conducting monetary policy, the idea of being able to establish any monetary rule once and for all just seems outlandish.[↩]

- Through the balancing effects of arbitrage activities by authorised resellers.[↩]

- This point is raised by Michael Pettis (https://carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancialmarkets/79396#comments).[↩]

- https://libra.org/en-US/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2019/06/LibraWhitePaper_en_US-1.pdf[↩]

- As raised by the ECB’s Yves Mersch (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2019/html/ecb.sp190902~aedded9219.en.html).[↩]

- Variation over the period May 8, 2014 to April 13, 2015.[↩]

- https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap73j.pdf[↩]

- The so-called “Three Refinements”.[↩]

- Set as the HKD 0.05 range around the central parity of HKD 7.8.[↩]

- Note that this operation followed a weak-side-triggered intervention by a few days, which caused the HKMA to buy HKD 3.12 billion from banks (the weak-side was still at HKD 7.8 at the time of the trigger, gradually shifting to 7.85 by the end of May).[↩]

- https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/publication-and-research/quarterly-bulletin/qb200509/ra2.pdf[↩]

- In November 2008 alone, the strongside CU was triggered 27 times, inducing the HKMA to sell over $104 billion HKD (approx. 6% of GDP) into the system (increasing the balance sheet to $158.0 billion by December 31, far exceeding the 2004 record high of around $55.0 billion).[↩]

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-dollar-explainer/why-is-the-hong-kong-dollar-probing-the-weak-end-of-its-band-idUSKCN1GL0KT[↩]

- Indeed, at any point one point of its existence, Argentina’s currency board regime violated at least one of the three criteria of an “orthodox” currency board, as defined by Hanke and Schuler (2002): to maintain a fixed exchange rate with its anchor currency; to allow for full convertibility (i.e. allow holders of the currency to move into or out of the anchor currency without restriction); and to fully back monetary liabilities of the currency board with foreign currency assets.[↩]

- https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2002/august/argentina-currency-crisis-lessons-for-asia/[↩]

- Bindseil (2019) in Central Banking before 1800 writes about the: “Temporary suspension of convertibility in a financial crisis to address risks of a run on the central bank, however with the credible commitment to restore convertibility”(page 25).[↩]

- IMF Working Paper Research Department. The Chicago Plan Revisited Prepared by Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof. August 2012.[↩]

- https://www.tnbusa.com[↩]

- Based on 3-months treasury bills.[↩]

- Analogously, reserves with the ECB and the Bank of Japan have a negative yield, while those with the Fed and the Bank of England are positive but extremely low and it is not clear that Libra would have access to the relevant central banks.[↩]

- Subsequently the price will depend on usage, since TIPS is priced on a “full cost recovery” basis.[↩]

- It is likely that, building on the huge network provided by Facebook. Libra could rely on very large wholesale bank intermediation in the form of authorised resellers.[↩]

- https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/conferences/html/20191126_payments_conference.en.html[↩]

- For an introduction, see https://bruegel.org/2018/12/can-virtual-currencies-challenge-the-dominant-position-of-sovereign-currencies/[↩]

- Currency boards in existence in 1990.[↩]

- ECCB countries are: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines.[↩]

- Here substituting “Stable coin issuing vehicle” with “Libra issuer” and “Stable Coin” with “Libra”. U. Bindseil (2019b) Central bank digital currency – financial system implications and control. Mimeo[↩]

- Numbers of the starting balance sheet are patterned on the euro area flow of funds.[↩]