The higher yield on Italian government securities could soon be a burden for the real economy

The Italian economy has been burdened for decades by a very heavy debt, whose cost crowds out other more socially useful expenses and impairs the country’s ability to reduce its stock of debt. In addition, the high debt negatively influences both consumers’ and investors’ expectations, as they are aware that they eventually have to bear its brunt.

The most effective way to reduce the burden of debt is to reassure those investing in the securities issued by the Italian state that their money is safe. The confidence of investors is measured by the spread between Italian and German government securities, the latter being seen as the safest assets. An increased spread means that the Italian state has to devote a larger amount of resources to compensate the reduced confidence of investors.

As documented in Figure 1, the spread had come down last spring to levels around 130 basis points, which one could deem consistent with the different fundamentals of the Italian and the German economy. The spread, however, has more than doubled since the Italian elections in March, as the fiscal prospects have deteriorated and the new government has managed to introduce doubts about the continued participation of Italy in the euro area, thus rekindling re-denomination risk – i.e. the risk of being repaid in devalued lira instead of solid euro.

Figure 1. Spread between 10 year Italian and German government bonds.

Source: Bloomberg

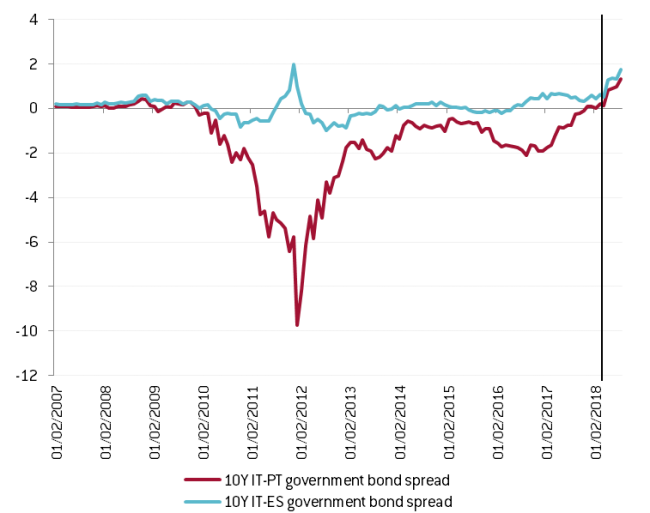

The comparison with German securities may be regarded as not fully appropriate, since the German economy and fiscal situation are so much stronger than those prevailing in Italy. But the comparison with two peripheral countries, Spain and Portugal, shows that the recent increase of the spread is an idiosyncratic Italian phenomenon: the yield of Italian securities is now much higher than those of the other two peripheral countries, while in previous years it was mostly close to that of Spanish securities and much lower than that of Portuguese bonds.

Figure 2. Spread between 10 year Italian and Spanish/Portuguese government bonds.

Source: Bloomberg

The Osservatorio dei Conti Pubblici Italiani, directed by Carlo Cottarelli, has estimated that the increased spread will cost a total of €6 billion to the Italian state in the remaining part of 2018 and 2019. Just to have a standard of comparison, this is close to 10% of what the Italian state annually spends on education.

But there is a potential additional burden coming from an increase of the spread, and thus from the cost of public debt. This potential cost is documented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. OIS rate, BTP yield and the cost of bank loans in Italy.

Source: Bloomberg, ECB

The figure reports three interest rates:

- The green line represents the interest rate on a two-year OIS (Overnight Index Swap) contract, which closely measures actual and expected monetary policy conditions, as determined by the ECB.

- The red line reports the yield on the two-year BTPs, heavily influenced by the ups and downs in the confidence of investors.

- The cost of bank loans, with maturity up to one year for Italian non-financial corporations, is represented by the light blue line.

In the figure, one sees that the yield on Italian government securities started to deviate from the monetary policy rate as the Great Recession intensified and the deviation assumed paroxysmal behaviour in the spring/summer of 2011.

At about the same time, the OIS rate signalled the renewed easing from the ECB. But in Italy the cost of bank loans for non-financial corporations, instead of coming down as monetary easing started to increase, was pulled up by the yield on BTPs.

Indeed, the yield on government securities is a bellwether: in a given jurisdiction, the state should be the best creditor and the cost of its borrowing should be lower than that for any other borrower – as one can indeed see, except for a short period, in Figure 3. Thus, the increase in the yield on government securities, pulling up the cost of bank credit, imparted a deflationary impulse onto the economy just when the ECB was trying to stimulate activity with lower rates, and this negative effect persisted for more than four years.

This is also visible in Figure 4, reporting the CDS (Credit Default Swaps) of three large Italian firms: ENEL, ENI and Telecom Italia. CDS report the cost of insuring against the failure of the three corporations and this cost was directly pulled up by the spread on Italian government securities.

Figure 4. Corporate CDS of ENEL, ENI and Telecom Italia (lhs) and the spread on BTP (rhs).

Source: Bloomberg

It is interesting to compare the Italian developments with those in Germany. Figure 5 reports the equivalent rates for Germany as in Figure 3 for Italy.

Figure 5. OIS rate, Bund yield and the cost of bank loans in Germany.

Source: Bloomberg

In the figure, we see that the yield on German securities very closely followed the OIS rate, and thus the ECB monetary policy, and that the cost of bank loans broadly followed the other two rates – thus smoothly transmitting the monetary policy easing to the economy. German firms were thus, unlike Italian ones, fully enjoying the lower cost of credit engineered by the ECB.

Again, it is useful to compare the Italian developments with those in Spain and Portugal. This is done in Figure 6. During the Great Recession, Spanish and Portuguese firms suffered, like their Italian counterparts, the consequences of the ballooning yield on government securities for the cost of bank loans. But no increase of the yield is visible in these countries over the last few months. Portuguese and Spanish firms should thus continue enjoying a low cost of bank loans, unlike what is likely to happen to Italian firms, unless the yield on Italian securities comes soon down.

Figure 6. OIS rate, government bond yields and the cost of bank loans in Spain and Portugal.

Panel A. Portugal

Panel B. Spain

Source: Bloomberg, ECB

In the light of the experience gained during the Great Recession, the increase of the yield on Italian securities observed since the elections is worrying. No effect on the cost of bank loans is visible as yet and this is not surprising, observing that this interest rate has intrinsically a much more inertial behaviour than the yield on government securities. But if the increase in the yield will persist, and possibly further deteriorate, the negative effect on the cost of bank loans and thus the deflationary effect on the economy will in all likelihood be visible. The real economy would then suffer, together with the Italian tax payers, the cost of the increased spread.

The Italian government should be aware of this risk and, to avoid both fiscal and macroeconomic costs, do all that it can to reassure investors that their money is safe. The 2019 budget law will be an important occasion to reassure investors. Unfortunately, there is little sign that the government, with the notable exception of Minister Tria, is even aware of the damages from higher yields on the fiscal and economic situation.

This post was written by Francesco Papadia and Inês Goncalves Raposo