The European Central Bank’s timid operational framework and what it is missing

Together with Giulia Gotti

Abstract

In March 2024, the European Central Bank published the results of a review of its operational framework. After discussing how the ECB operational framework has changed since the Great Financial Crisis, we provide an assessment of the review, which we deem as premature, and highlight some gaps it has not resolved. First, the choice of a hybrid system is attractive, but needs a precise specification. Second, the review did not specify the timing of the introduction of structural long-term refinancing operations and a structural portfolio of securities. We find that these measures should be implemented when the level of excess liquidity reaches between €1.3 trillion and €2 trillion, projected between mid-2026 and late 2027. Finally, as the introduction of a digital euro could impact bank liquidity, it is crucial to design a framework that can flexibly increase the supply of central bank liquidity

1. Introduction

Friedman and Kuttner (2010) noted some 15 years ago that very little research: “addresses what central banks actually do.” Similarly, Borio (2023) regretted the limited interest in the actual implementation of monetary policy. We agree that this is a shame because implementation issues, summarised in a central bank’s operational framework, determine the effectiveness of monetary policy and even the best strategy will fail if not implemented effectively.

This paper answers, for the European Central Bank, the question of ‘how do they do that?’ Taking into account the changes that have taken place in the last 15 years or so, it describes how they did it, how they do it and how they could do it in the future.

Section 2 briefly describes and assesses the framework prevailing before the Great Financial Crisis. In section 3, we show how the implementation of monetary policy has changed with the financial crisis, even if, formally, the operational framework did not change. Section 4 describes the current situation, while section 5 lists the criteria to assess different frameworks. In section 6 we evaluate the ECB’s March 2024 review of its Operational Framework (ECB, 2024), which Demertzis and Papadia (2024) have qualified as timid, leaving many gaps to be filled. In section 7, we set out the features that, in our view, should prevail in a future operational framework and thus fill the gaps the ECB’s March 2024 review left open.

Our main findings are:

- The ECB review was premature, since there was no sufficient information to precisely design the future operational framework.

- There is no need to design now the future operational framework since the ongoing reabsorption of excess liquidity will not disturb the conduct of monetary policy.

- Monetary policy has returned to the traditional and much more effective calibration of interest rates, rather than the management of the central bank balance sheet in the guise of quantitative easing or tightening (Välimäki, 2023).

- The choice of one or other framework has no undue effects on the monetary policy stance. The separation between monetary policy and liquidity conditions now again prevails and, just by changing interest rates, any desired monetary policy stance can be achieved. Thus, the preferences of doves for keeping an abundance of excess liquidity – or reserves – in the so-called floor approach, and those of hawks for eliminating excess liquidity, in the so-called corridor approach, are misplaced.

- There are many criteria to assess different implementation frameworks, but it is not possible to rank them, given their extensive trade-offs.

- The so-called hybrid framework, working with ample but not abundant excess liquidity, thus combining aspects of the floor and the corridor approaches, is potentially attractive, but without a precisely defined design is an amorphous set-up.

- Our view of how a hybrid approach could be specified, thus contributing to filling the gaps left open by the ECB review, foresees the following features:

- The area where excess liquidity would start to be scarce and the risk of the overnight rate ‘taking off’ from the deposit facility rate (DFR) can be estimated at between €1.3 trillion and €2 trillion, with respect to the current level of about €3.7 trillion1, corresponding to 35 percent and 54 percent respectively of current bank deposits.

- We estimate that the levels of excess liquidity mentioned in the previous point will be reached in mid-2027 and March 2026, respectively.

- Three years is a plausible maturity for both longer-term refinancing operations and the average of the portfolio of securities held for monetary policy purposes.

- In terms of composition, the portfolio of securities held for monetary-policy reasons could be the same as the current one resulting from quantitative easing, including corporate, sovereign, covered and international institutions’ bonds and asset-backed securities.

- While weekly main refinancing operations could be conducted at a fixed rate 15 basis points above the DFR, in longer-term refinancing operations, all demands would be satisfied and banks would commit to pay the average of the DFR over the duration of the lending, plus a liquidity premium derived from market quotations.

- The ECB could contribute to greening the economy by favouring green bonds or sustainability-linked bonds and by applying more favourable conditions to green longer-term refinancing operations.

- Non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) should be admitted, in some way, to the ECB’s deposit facilities, even if under different conditions to banks.

- The foreseen introduction of a digital euro (central bank digital currency, CBDC) could, in the case of financial crises, impact banks` liquidity even if the envisaged limits make it unlikely that the central-bank digital currency will become a major source of outflows in normal circumstances. This suggests designing a framework that can flexibly increase the supply of central bank liquidity and keeping a larger rather than a smaller level of excess liquidity in the system.

2. The pre-2008 operational framework

The operational framework is the set of instruments that allows the implementation of the monetary policy stance determined by the ECB Governing Council. By performing financial transactions within the parameters of the framework, the ECB steers short-term interest rates in the pursuit of price stability.Before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the ECB operational framework was defined as the corridor approach and had three main components: three policy interest rates, open market credit operations and compulsory but remunerated reserves.

The corridor approach is so named because the ECB sets policy rates on its standing facilities, which establishes the upper and lower limits within which the short-term market interest rate fluctuates, much like the walls of a corridor. These limits, also known as the floor and the ceiling, are represented respectively by the rates of the two standing facilities: the deposit facility rate (DFR) and the marginal lending facility rate (MLFR). At the deposit facility, counterparties can deposit excess liquidity overnight, remunerated at the DFR. The marginal lending facility, instead, provides banks with liquidity to meet unexpected daily liquidity needs at a penalty rate, the MLFR. The DFR represents the floor of the corridor, because no bank would lend for less than the rate the ECB offers for excess liquidity. Similarly, the MLFR is the ceiling of the corridor, as no bank would borrow at a rate higher than that at which the ECB is willing to lend liquidity. The width of the corridor, ie the difference between the ceiling and the floor, used to be 200 basis points, but the short market rate stayed very close to the centre of the corridor.

Having established these boundaries, liquidity management was crucial in positioning the market rate within the corridor. Two key components come into play. The first is reserve requirements. Before January 2012, euro-area banks had to keep 2 percent of their short-term deposits in Eurosystem accounts. The reserve requirements needed to be respected on average over a monthly maintenance period (as opposed to daily). This implied that, in days of low liquidity, banks could keep lower reserves and offset this on days of more abundant liquidity. By doing so, banks stabilised interest rates, mitigating the effects of short-term liquidity shocks (Papadia and Välimäki, 2018; Hartmann and Smets, 2018).

The second element was open market operations, which took the form of main refinancing operations (MROs) and longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs). The latter are credit operations with three-month maturities. MROs are weekly auctions of collateralised loans with a maturity of seven days, where the minimum bid rate constitutes the policy rate, MROr, set by the Governing Council in the middle of the corridor. Prior to October 2008, the ECB fixed the quantity of liquidity to be allocated according to its estimates of so-called autonomous factors. Autonomous factors, including government deposits, banknotes and net foreign assets, were the main sources of uncertainty in determining the banking system’s liquidity needs (ECB, 2001). In addition to reserve requirements, autonomous factors determined the liquidity demand that banks must satisfy by the end of the maintenance period.

In this context, the ECB implemented a liquidity management strategy based on the benchmark approach, in which, by accurately forecasting the banking system’s liquidity needs, the central bank provided just enough liquidity to meet the liquidity deficit (Papadia and Välimäki, 2018). This ensured that the market rate remained in the middle of the corridor, close to the MROr, and that the level of excess liquidity was negligible. Since the ECB provided only the necessary liquidity to meet banks’ needs, there was zero excess liquidity supply. Conversely, as banks could meet their needs with the provided liquidity and found it costly to hold excess liquidity, there was also zero excess liquidity demand. This framework configuration resulted in a scarce level of liquidity, often referred to as a scarce reserve system. It should be noted that the terms ‘excess liquidity’ and ‘excess reserves’ are used interchangeably to describe the deposits in excess of reserve requirements that banks hold with the central bank.

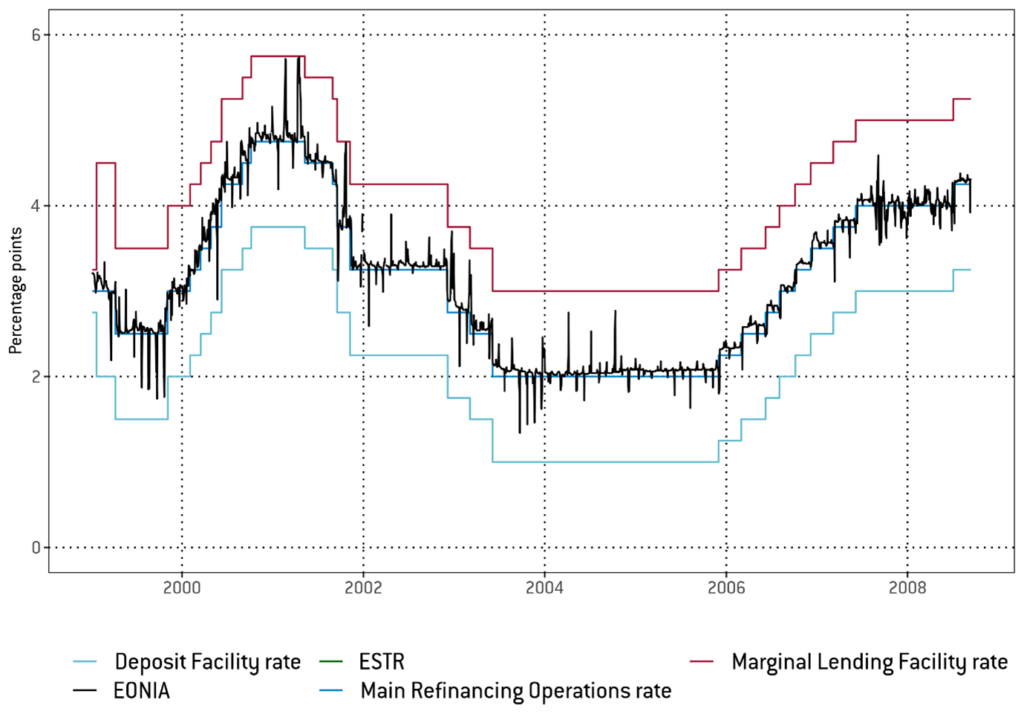

Finally, another two characteristics of the operational framework were the ample collateral and the eligibility criteria for banks to access ECB facilities. Overall, until late 2007, the corridor system effectively fulfilled the ECB’s operational targets. First, the ECB maintained overnight rates close to the middle of the corridor (Figure 1), ie to the MROr (Schnabel, 2023a), while keeping excess liquidity negligible. Additionally, liquidity conditions in the market, including the ability to liquidate assets and fund maturity mismatches, remained favourable. Lastly, by steering the short-term interest rate, the ECB could influence effectively the longer and riskier term rates that affect the real economy, ensuring the smooth transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. However, with the onset of the GFC, these conditions no longer held, and the ECB implemented a series of measures, leading to the abandonment of the corridor system.

Figure 1: ECB policy rates and market rates before the GFC

Source: Bruegel based on ECB data.

3. Post-2008 developments

At the beginning of the GFC, the three aspects – 1) good liquidity conditions, 2) short-term rate stability, and 3) effective transmission of monetary policy – no longer prevailed. The policies undertaken to counteract the crisis led to an explosion in central bank excess liquidity, which eventually transformed the operational framework into a floor system.

3.1 Liquidity conditions

In August 2007, the early stages of the financial crisis saw significant turbulence in money markets, leading to a surge in demand for central bank liquidity to replace market liquidity. The collapse of the US subprime mortgage market triggered a reassessment of risk, creating liquidity tensions that impaired the ability of banks to liquidate their assets. This also affected funding liquidity, or the ability of banks to manage liquidity mismatches. With both market and funding liquidity frozen, banks relied increasingly on the central bank as the primary source of liquidity. The demand for central bank liquidity surged dramatically in summer 2007 and, by the end of the period, it was clear that the central bank could no longer provide liquidity solely to offset autonomous factors (Mercier and Papadia, 2011).

As banks’ demands for liquidity became unforecastable, exceptionally, on 9 August 2007, the ECB offered full allotment to the bids made at a fixed rate in an ad-hoc fine-tuning operation, reaching an amount that, at the time, looked huge: €95 billion, reflecting the liquidity stress in the money market.

In the autumn of the following year, after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the financial crisis entered its acute phase. In summer 2009, then-president of the ECB, Jean Claude Trichet, defined the set of non-standard measures taken in this phase of the crisis as “enhanced credit support” (Trichet, 2009). This approach consisted of four pillars. First, from October 2008, all operations were conducted under full-allotment tender procedure, where, instead of auctioning a predetermined amount of liquidity in the weekly operations, the ECB met any requests for liquidity made by banks, letting the banks determine how much liquidity to take from its refinancing operations at a fixed rate set as the MROr. Second, the first covered bond purchase programme (CBPP1) was launched. Third, the list of assets eligible for collateral was extended and the threshold of asset quality was lowered from A- to BBB-. Finally, the ECB lengthened the maturity of LTROs, first to six months and then to one year. These responses contributed, together with an easing of fiscal policies, to the initial economic recovery from the GFC. Looking at the issue from a different perspective, the central bank intermediated funds that the private sector was no longer able to intermediate (Hartmann and Smets, 2018; Papadia and Välimäki, 2018).

3.2 Interest rate stability

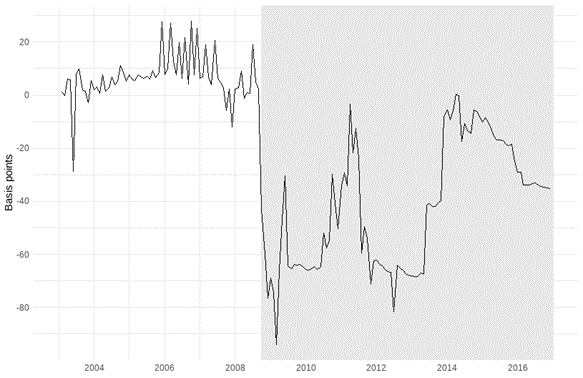

An immediate consequence of the liquidity crisis was the instability of short-term interest rates. As mentioned above, the unpredictability of banks’ demands for liquidity made it more difficult for central banks to counter these fluctuations. Consequently, the Euro Overnight Interest Average (EONIA), the interest rate charged in the interbank market, experienced significant volatility and began to diverge from the MRO policy rate. These effects can be seen in Figure 2: as the stable relationship between EONIA and MROr no longer prevailed.

Figure 2: Spread between EONIA and the MROr (basis points)

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg. Note: The shaded area corresponds to the period after the beginning of the GFC.

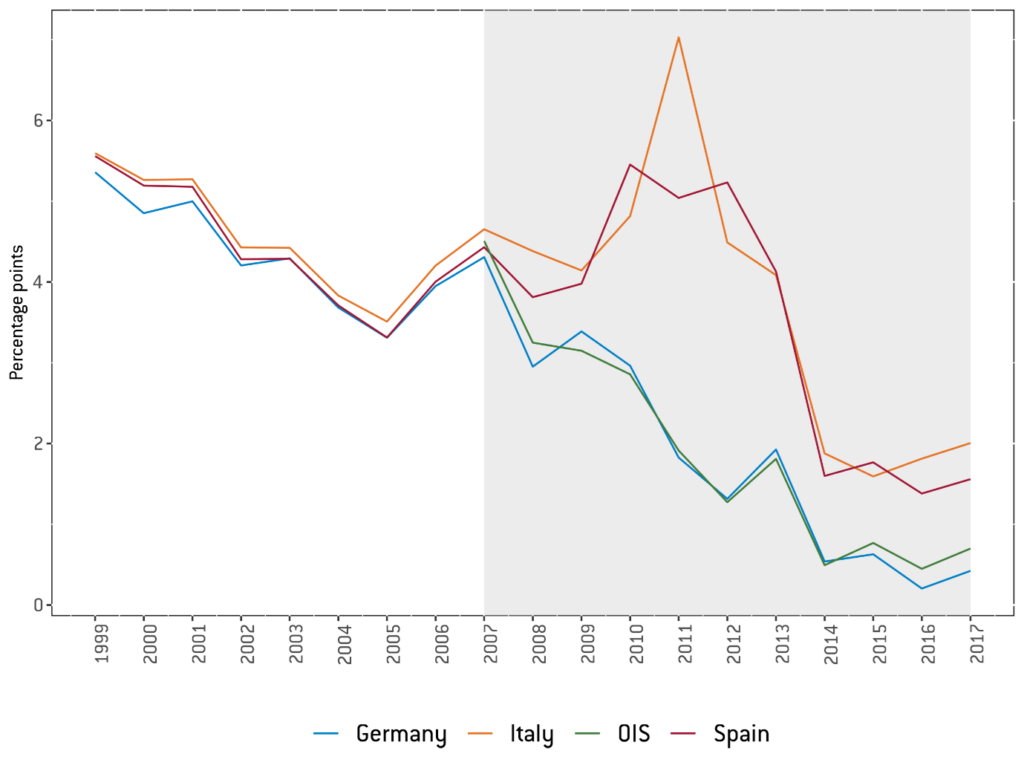

3.3 Orderly spreads and monetary policy transmission

Another feature of the operational framework before the crisis, ie the transmission of impulses from the overnight to longer-term and riskier interest rates, which had resulted in orderly, even if too low, spreads, was lost. Starting in 2008, as the crisis built up in Europe, the spreads between the short-term and the long-term/riskier interest rates widened. In particular, in peripheral countries the cost of financing for governments increased (Figure 3), leading to a generalised interest rate increase (Papadia and Välimäki, 2018) thus causing a tightening in monetary conditions in these countries, despite the easing stance of the ECB.

Figure 3: Yields on Italian, Spanish and German 10-year government bonds and the risk-free 10-year Overnight Index Swap rate.

Source: Bloomberg. Note: The shaded area corresponds to the period after the beginning of the GFC.

A disorderly transmission of spreads impairs the transmission of monetary policy, affecting the ability of the ECB to uniformly impact the economy across the euro area. The collapse of money market activity and soaring spreads prevented rate cuts from being passed to the economy, causing the ECB to lose control of the short-term interest rate and leading to a breakdown in the transmission chain, which fundamentally impaired the effectiveness of monetary policy (Mongelli and Camba-Mendez, 2018).

In response to the fragmentation in sovereign markets, in 2010 the ECB introduced the Security Markets Programme to address malfunctioning bond markets in Greece, Portugal and Ireland. The programme was revamped in the same year due to financial stress in Spain and Italy, ultimately reaching a nominal value of €218 billion (Hartmann and Smets, 2018). Whether the programme was successful is still disputed today.

By the end of 2011, during the euro-area crisis, the ECB had introduced more non-standard measures: very long-term refinancing operations (VLTRO) with three-year maturity and the option of early repayment after one year, followed by a second programme in 2012 totalling more than €1 trillion. Minimum reserve requirements were lowered to 1 percent from 2 percent and the list of eligible collateral was expanded again. With these measures the ECB aimed at giving banks funding certainty and at easing credit conditions. However, as a direct consequence of the VLTRO, banks in the periphery of the euro area – particularly in countries experiencing sovereign stress – used the newly acquired liquidity to purchase national bonds under the ‘moral suasion’ of their national governments. This behaviour, as explained by Véron (2024), reinforced the sovereign-bank loop and threatened financial stability. Against this background, in 2012 financial tensions rose again because of weak growth and fiscal developments.

In July 2012, Mario Draghi, the ECB president, reassured the markets with his famous “whatever it takes” speech. A few days later the Governing Council announced the introduction of outright monetary transactions (OMTs), conditional on an appropriate macroeconomic adjustment attached to a European Stability Mechanism programme, a back-stop measure that unfortunately created stigma. OMTs, although never activated, are credited with reducing sovereign spreads as market participants gained the confidence that states in stress would get assistance (Mongelli and Camba-Mendez, 2018).

3.4 Zero lower bound

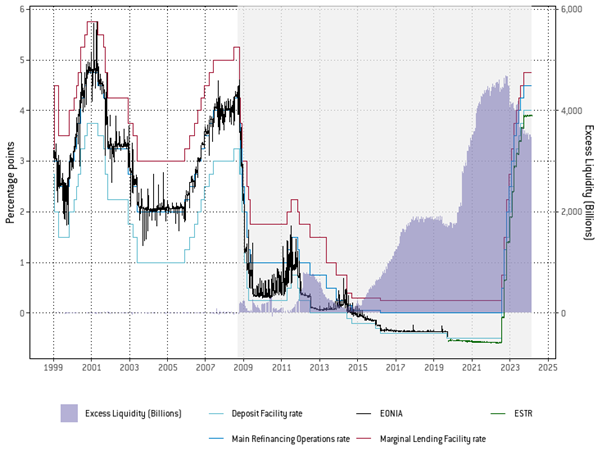

During the later stages of the euro-area crisis, the ECB intervened not only by addressing liquidity issues but also by lowering interest rates. As shown in Figure 4, the ECB brought interest rates down from 4.25 percent in summer 2008, with an interruption in 2011, to zero in July 2012 and then below zero in June 2014 – the second time a major central bank, after the Bank of Japan, set a negative policy rate.

Fig. 4: ECB key policy rates, overnight market rates (RHS, percentage points) and excess liquidity (LHS, € billions)

Source: Bruegel based on ECB and Bloomberg. Note: The shaded area corresponds to the period after the beginning of the GFC.

From 2011, to ease monetary policy further, the ECB fell back on a set of unconventional measures that impacted greatly the operational framework, injecting huge amounts of excess liquidity through targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) and the Asset Purchase Programme (APP).

The TLTRO programmes consisted of a series of operations, the size of which was proportional to the share of banks’ outstanding loans to households and corporations at very low borrowing costs. In particular, TLTRO-II adopted in 2016 was priced at the DFR, which at the time was negative. These programmes contributed to the increase in excess liquidity in the form of bank reserves held at the central banks. At the same time, under the APP, the ECB implemented substantial portfolio management measures to provide monetary stimulus through quantitative easing (QE). The APP targeted both private and public securities with monthly purchases and the stock of APP holdings peaked in 2022 at €3.4 trillion with, as a major consequence, an increase in the size of the ECB balance sheet. The implementation of QE marked a major innovation in monetary policy as the ECB used balance sheet management as the primary tool, not only to provide liquidity but to stabilise the interest rate within the corridor, and to regain control of short-term rates, bring order in the spreads and to further ease monetary policy at the zero lower bound (Papadia and Välimäki, 2018).

3.5 Conclusion

The ‘non-standard’ policy measures implemented during the crisis and the subsequent low-inflation period allowed the regaining of control of short-term rates, stabilising spreads and monetary easing beyond the lower interest rate bound.

On the other hand, they caused a substantial increase in the ECB’s balance sheet, primarily through its monetary policy portfolio of securities, and a corresponding rise in the amount of excess liquidity held as reserves at the ECB (Papadia and Välimäki, 2018).

In 2008, the abundance of excess liquidity brought the market rate towards the bottom of the corridor, as shown in Figure 4. Following the implementation of the APP in 2014, the market rate settled steadily at the floor, effectively making the ECB’s operational framework a floor system.

The shift in the framework had unintended consequences. First, the separation between fiscal and monetary policy became blurred and concerns were raised about monetary financing of budget deficits. QE and the lowering of yields that was sought inevitably altered the pricing and allocation of risk. Additionally, ECB purchases created scarcity of high-quality collateral, which affected bond liquidity and market functioning, as the central bank’s large holdings reduced the availability of bonds for trading. Finally, the abundance of excess liquidity reduced activity in the interbank unsecured money market until it eventually came to a virtual halt (Borio, 2023; Schnabel 2023). Borio (2023) and Borio et al (2024) added a more general negative, consequence from the abundance of reserves: their transformation from settlement medium to store of value, making them sensitive to relative returns and thus less stable. Indeed, Borio argued that the apparently huge and unstable demand for reserves was, to a good degree, caused by the very abundant supply from central banks. A return to a situation in which reserves are scarce, meaning that excess liquidity is eliminated, would in turn deflate the demand for reserves and ensure that, in all circumstances, liquidity management has no effect on interest rates other than the overnight rate.

4. Situation in mid-2024

The most relevant factors for the implementation of monetary policy prevailing in mid-2024 are the following:

- Interest rate changes are again the dominant interest rate tool;

- There is great uncertainty about the level of the natural rate of interest;

- Quantitative tightening is progressing gradually, but

- Both the overall size of the ECB balance sheet and excess liquidity remain very large;

- Liquidity is still concentrated in the banks of core jurisdictions, but the degree of concentration is slowly decreasing;

- The turnover in the money market is mostly due to non-bank-financial-institutions;

- Bank liquidity demand is very difficult to estimate;

- Overnight interest rates have often been lower than the DFR, undermining its role as floor of the interest rate corridor.

We illustrate these different factors in turn.

While central bank balance sheet management was, for many years, the dominant monetary policy tool, the ECB reacted in July 2022 to the flare-up of inflation with sharp interest rate increases (Figure 4). Since then, the interest rate has been again the main monetary policy tool. Both during the tightening phase, between July 2022 and September 2023, and since the first rate cut, in June 2024, ECB announcements and comments, as well as observers’ attention, have concentrated on interest rates, leaving balance sheet changes, ie quantitative tightening, in the background.

The renewed interest in interest rates has refocused attention on the so-called natural rate of interest, that is the rate at which both inflation and economic activity are stable at their long run values. This rate is of critical importance because the difference between it and the actual rate of interest determines the monetary policy stance and because the natural rate indicates where rate cuts would stop. At the same time, the natural rate is unobservable,and its estimates are very uncertain: Brand et al (2024) presented a range of estimates between –0.5 and more than +1.0 percent.

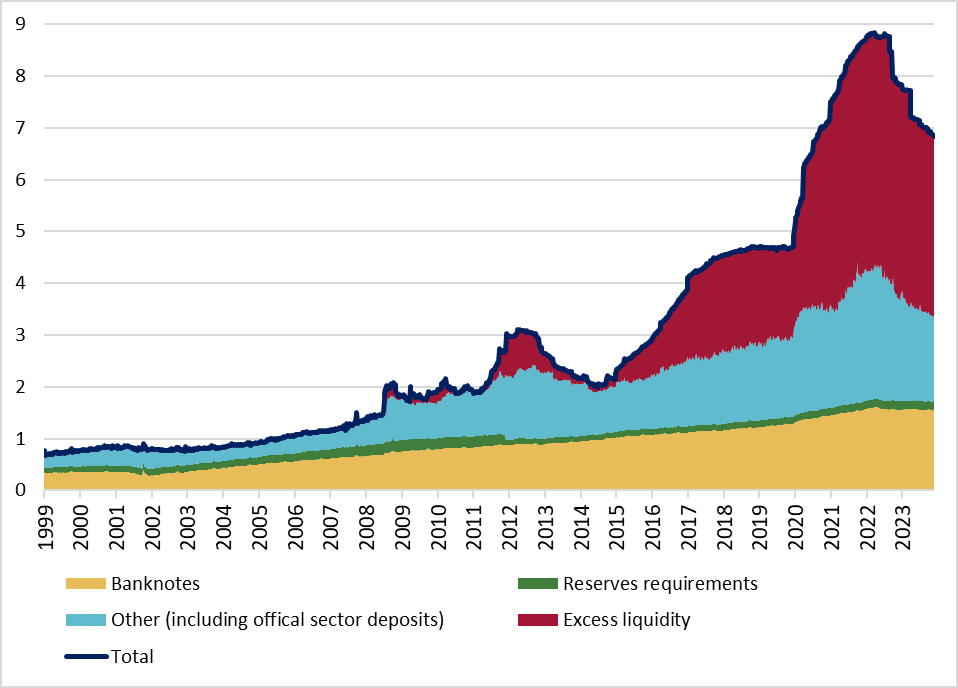

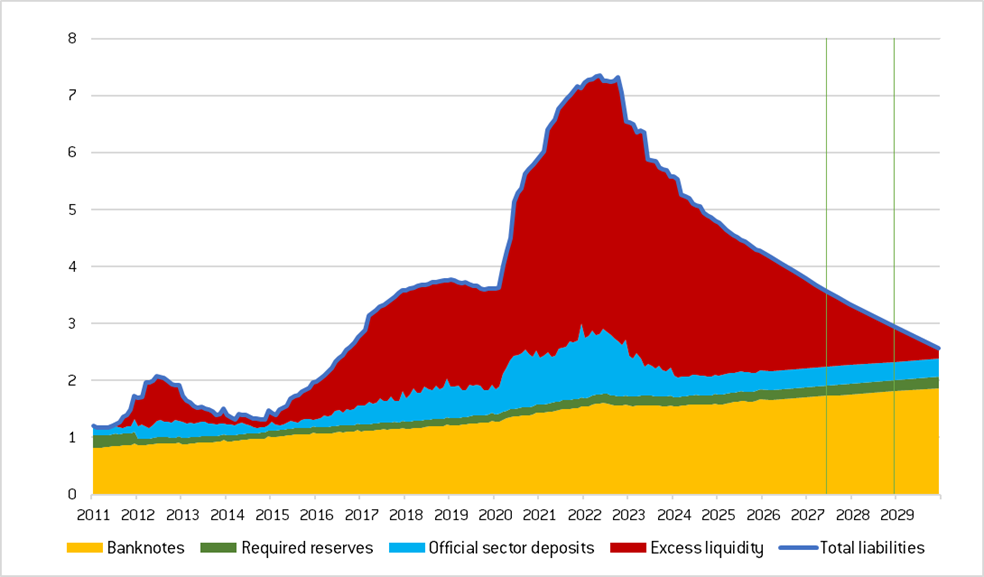

Quantitative tightening has started, together with the anticipated reimbursements of TLTRO, to reduce the size of the ECB balance sheet, particularly of excess liquidity. Looking at Figure 5, the levels of the two variables remain, however, very large at €6.8 trillion and €3.7 trillion respectively.

Figure 5: ECB balance sheet, liabilities (€ trillions)

Source: ECB

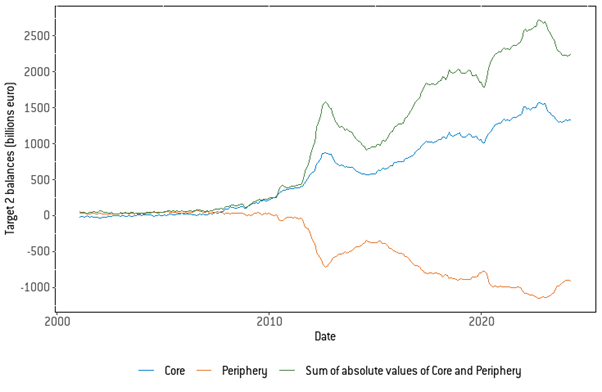

Another phenomenon accompanying the huge expansion of excess liquidity after the beginning of the GFC was its very uneven distribution across banks and jurisdictions. TARGET2 balances2, reported in Figure 6, are an indicator of the concentration of liquidity in the core of the euro area and away from the periphery, after 2008. Increasing TARGET2 balances indicate how central bank liquidity substituted for market liquidity that was flowing away from banks in the periphery, before starting a very gradual reduction in mid-2022.

Figure 6: TARGET2 balances of core vs periphery (€ billions)

Source: Bruegel, based on ECB. Note: Core is the sum of Germany and Luxembourg, periphery is the sum of Spain and Italy.

Another important characteristic of the environment within which monetary policy is currently implemented is the very limited turnover in the unsecured interbank money market. This is a result of the combination of two different phenomena, documented by Schnabel (2023a; 2024):

- The prevalence of secured (repo) transactions among banks;

- The overwhelming importance of non-bank-financial institutions in the money market.

There is a unanimous view that there is high uncertainty about central bank liquidity demand from banks. Välimäki and Niemela (2023) noted that the ability and willingness of banks to distribute liquidity is heavily impaired and this leads banks to hoard liquidity, making it impossible to estimate their demand. Schnabel (2023a) made a similar point and added that regulatory changes, in particular the Basel III Liquidity Cover Ratio, incentivise banks to increase their demand for bank reserves to use them as high-quality liquid assets. Also Borio (2023) recognised that the difficulty in estimating the demand for liquidity from banks is a reason, non-conclusive in his view, to retain an operational framework with an abundant supply of reserves. Even if, as Borio et al (2024) argued, there is an element of endogeneity in the demand for reserves, in the sense that an abundant supply contributed to it, the central bank has to deal with the demand that exists in the system, while trying to deflate it by lowering supply may carry great risks of instability.

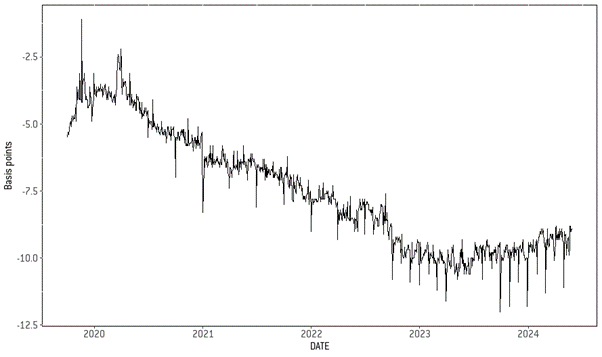

The last main characteristic of the current situation is that the rate on the money market is below that of the deposit facility, leading to a so-called ‘leaky floor’. This phenomenon occurs because non-banks cannot deposit their liquidity with the ECB and therefore must deposit it with banks that apply a cut to the offered return. This phenomenon reduces the precision of the control of the overnight rate.

Figure 7: Spread between deposit facility rate and overnight rate (basis points)

Source: Bruegel based on ECB.

5. Choice criteria

While the ECB has the overriding objective of price stability, there are many frameworks to pursue this objective and their assessment requires a fine criteria grid.

Before illustrating these criteria, it is necessary to assess whether the desired tightness, or ease, of monetary policy can be pursued with different operational frameworks.

5.1 The separation principle applies again

A positive answer to the question of whether, in normal conditions, the operational framework is neutral with respect to the monetary policy stance3 can be given by recalling the ‘separation principle’, evoked by the ECB in the initial phases of the financial crisis.

This principle was defined in 2008 by then ECB President, Jean-Claude Trichet: “The ECB makes a clear separation between, on the one hand, the determination of the monetary policy stance and, on the other hand, its implementation using liquidity operations” (Trichet, 2008). The monetary policy stance is defined by the level of the interest rate while liquidity management steers market rates towards the policy rate.

Schnabel argued in 2023 that the separation principle became unsustainable when liquidity management, and in particular asset purchases, started to be used extensively for monetary policy purposes (Schnabel, 2023b). Thus, one sufficient condition for the non-applicability of the separation principle is when the central bank explicitly uses liquidity management to steer monetary conditions. Beyond the intentions of the central bank, the separation principle does also not apply if market participants see an influence on monetary conditions of changes in liquidity conditions.

Neither of these conditions apply since QE was stopped: the ECB stresses that monetary policy concentrates exclusively on interest rates. Market participants concur fully with this view, paying little attention to liquidity changes4.

A possible confusion must be dispelled about the term ‘separation principle’. Here, as explained, it is meant as the separation of monetary policy, consisting of interest rate calibration, from liquidity management. Another separation principle is often invoked talking about the ECB – between monetary policy and bank supervision. The Bundesbank, in particular, feared that putting supervision in the same institution as monetary policy could create conflicts: the ECB might prioritise bank stability even if that could affect price stability. Institutional separations were then created to deal with this risk. Experience shows that, in practice, the ECB managed to carry out the two functions without conflicts and confusion.

5.2 Does the choice of an operational framework influence the monetary policy stance?

A positive answer to this question is given by Altavilla et al (2023). They started their reasoning by importing into the European discussion the concepts of borrowed and non-borrowed reserves, originally developed in the US. Borrowed reserves are those that banks obtain by accessing a central bank lending facility: in the ECB case, basically the MRO and LTRO. Non-borrowed reserves are those resulting from purchases of assets by the central bank, in the ECB case mostly under the APP and PEPP. Altavilla et al (2023) however, also added reserves obtained from TLTRO, even if literally they are indeed borrowed. This point is expanded below.

The main point of Altavilla et al (2023) is that non-borrowed reserves, unlike borrowed reserves, expand bank lending and thus ease monetary conditions.

In our understanding, the distinction between borrowed and non-borrowed reserves is analogous to the distinction between passive and active ECB liquidity management5 as well as between demand-determined and supply-determined liquidity provision.

Our basic point is that the distinction between borrowed and non-borrowed reserves is blurred and is insufficient to choose one or another operational framework. The argument about the blurred distinction between borrowed and non-borrowed reserves can be made in four points.

- While Altavilla et al (2023) qualified the holding of liquidity provided by non-borrowed reserve as involuntary, there is no obligation to sell securities to the ECB under QE operations. Banks will do it only if the price at which they sell bonds equalises the risk-adjusted, expected return from holding the bond with the expected return from holding reserves, including a convenience yield for the latter.

- The assimilation of liquidity obtained from the TLTRO to that deriving from non-borrowed reserves, mentioned above, reflects the fact that the ECB strongly incentivised borrowing from the TLTRO, in terms of cost and maturity. The decisive issue is not whether reserves are borrowed or non-borrowed, but whether the ECB incentivises banks to borrow. This was done by the ECB lengthening the maturity of its long-term operations and reducing their cost until it resulted in a subsidy. Between the MRO and the TLTRO, there is a continuum of progressively more favourable conditions, not a partition between borrowed and non-borrowed reserves.

- The “reluctance” to use standing facilities, or stigma, recalled by Altavilla et al (2023), visible in the US before the crisis, has been much less prominent in the euro area (Brandao-Marques and Ratnovski, 2024), only surfacing during the financial crisis. If borrowing from the central bank is the normal way to get liquidity, as was the case before the financial crisis, there is no stigma.

- No one forbids a bank from borrowing from the ECB and having liquidity in its balance sheet instead of just an option to borrow from the standing facility. And the cost to do this will be low if the interest rates on the borrowing and lending facilities are close.

5.3 Potency of interest rate changes vs. balance sheet management

Another way to conclude that liquidity management and the monetary policy stance are normally separate in practice is to look at the elasticities of interest rate and balance sheet changes with respect to inflation. The effects of balance sheet changes on inflation are much smaller than those of interest rate changes (see Appendix 2). Thus, when not constrained by the lower bound, interest rate changes are a much more powerful tool to control inflation than balance sheet changes and the effect of liquidity management on the monetary policy stance is small and the separation principle, does, in practice, hold.

Having established that any degree of tightness or flexibility in monetary policy can be obtained with whatever framework, one must define the criteria to choose among the very many possible frameworks. The criteria presented below create many trade-offs, which complicates the choice of one or the other operational framework.

5.4 Criteria to choose an operational framework

The criteria are classified into three categories: first, and foremost, effectiveness of monetary policy; second, central bank independence; third, financial stability and efficiency.

5.4.1 Effectiveness of monetary policy

- Overnight interest rate control

The first criterion to assess an operational framework is whether it grants precise control of the overnight interest rate in terms of variability (in the sense of variance) and of distance from the policy rate. - Transmission along the yield curve and across countries (spread)

The overnight rate is the first link in the transmission of monetary policy. Monetary policy requires, however, adequate influence also over the entire yield curve, since macroeconomic variables are affected by rates longer than overnight. Analogously, the ECB wants its monetary policy to impact similarly all countries in the euro area. - Ability to expand again the balance sheet if needed

Quantitative easing proved useful when the interest rate lower bound was reached. It is unclear whether it could again be necessary to have recourse to QE and more generally to liquidity management. This will depend, first, on how high the natural rate of interest is; and second, on whether there will be market dysfunctions requiring the provision of exceptional amounts of liquidity, as during the financial crisis. Given the uncertainty about both issues, it is preferable to have an operational framework that could easily accommodate a return to QE. - Robustness in the face of uncertainty

Uncertainty about the natural rate of interest and about the demand for liquidity from banks are critical, but there are other uncertainties: first, the effect on the economy of climate change, both in terms of changes to fundamental economic parameters and of the consequences of mitigation and adaptation measures; second, the consequences of changes in globalisation patterns. A monetary policy implementation framework that would be robust against these and other uncertainties would be preferable to one for which performance depends on a specific set-up of circumstances. - Interbank distribution of reserves

Since the financial crisis starting in 2007-2008, liquidity has been very unevenly distributed across banks. Indeed, the distribution has also been uneven across jurisdictions, as examined in section 4. Which operational framework would be better able to cater for the uneven liquidity distribution? - Non-bank financial institutions and the money market

As recalled in section 4, non-bank financial institutions are important participants in the euro money market. This is not surprising given their growing intermediation activities. What is the best way to take this increased importance into account? - The occurrence of stigma

The reluctance to borrow from central bank facilities can cause the money market rate to exceed the rate at which the central bank is willing to fund banks: de facto this is no longer a ceiling for money market rates. An operational framework not generating stigma is preferable to one subject to it.

5.4.2 Central bank independence

- Central bank profit and loss and their repercussion on public finances

While central bank profits and losses are not decisive for the conduct of monetary policy, it is preferable if the central bank avoids persistent losses and, indeed, normally achieves positive rather than negative financial results (Chiacchio et al, 2018). - Blurred border between budgetary and monetary policy

Monetary and budgetary policy are intrinsically connected through the consolidated budget of the public sector. Still, the responsibilities of the two policies should be clearly distinguished, with monetary policy devoted to price stability and not to the funding of the budget deficit. The operational framework should strive to maintain the border between the two policy domains as clearly as possible. - Protection from political pressure

The ECB statute provides strong protection against political pressure. However, tension should be avoided between central bank independence and a desire from political bodies to reduce it. Of course, the point, covered above, about the blurred border between fiscal and monetary policy, is a potential vulnerability, but there could be others, for instance the remuneration of government deposits and the distribution of ‘dividends’ from the central bank. Generally, the broader the range of activities the ECB engages in, the greater the risk of political pressure. This is a point relevant also for the green issue, dealt with below. - Protection from financial market capture

Central bank independence from the private sector, particularly the financial sector, must also be ensured. A relevant area in this respect would be the cost of central bank refinancing, the remuneration of excess and required reserves. - International aspects

The ECB has abandoned its ‘neither encourage nor discourage’ attitude towards the international use of the euro and contributes to the policy of EU institutions to promote it. This requires being ready to consider its consequences for the conduct of monetary policy. - Green finance

The EU has embarked on an ambitious and necessary strategy to deal with climate change. The ECB should contribute to this, even if it can only play a subsidiary role in this endeavour. Many proposals have been made for the ECB to support climate action, and the ECB has already started taking climate issues into account in its operations. In choosing one or the other operational framework, implications for climate action should also be considered (Välimäki and Niemela, 2023).

5.4.3 Financial stability and efficiency

- Financial and price stability often coincide. What the central bank should do in pursuit of the former objective will, most of the time, also help with the second. But cases of dilemmas can emerge. Can one or the other operational framework be more conducive to financial stability whenever the use of the interest rate to pursue it would be difficult because of a dilemma?

- Central bank balance sheet imprint on financial market

Central bank action has necessarily an influence on the financial market: monetary policy consists of raising or lowering interest rates, with a pervasive effect on the financial part of the economy. However, this influence should avoid undesired effects. For instance, an operational framework requiring large holding of securities by the central bank could produce a scarcity of collateral and too few bonds available for trade. - Size of the (interbank) money market

Some operational frameworks favour a thriving money market; others tend to crowd it out. In assessing the size and functioning of the money market it is useful to divide it into two kinds of participants: banks and non-banks. The two categories of intermediaries differ in terms of access or non-access to central banking facilities, absence or presence of liquidity regulations, degree of mismatch between assets and liabilities, capital endowment and capital regulations. Overall, an operational framework fostering an active money market, in which both banks and non-banks are active, is desirable. - Digital euro

The issuance of a retail CBDC could potentially disintermediate banks, reducing their liquidity. In normal times any disintermediation effect should be limited. Still, in times of crisis, the flight toward the security of a liability issued by the central bank could be both large and sudden. Liquidity provision should be flexible enough to accommodate changes in liquidity conditions arising from a CBDC, in case tensions appear in the money market and possibly beyond.

6. Different options

6.1 Stay with floor system

One candidate for the steady state regime is a floor system, with ample or even abundant liquidity keeping the overnight rate close to the DFR. This is the system implemented by the Fed. The floor approach can come in two different variants.

- Supply-based

This is the obvious variant, as the central bank actively provides liquidity to the market using outright securities purchases, akin to QE, and would continue to have a large portfolio of assets for monetary policy purposes. - Demand-based

In the demand-based floor approach, as used by the Bank of England, the central bank regularly offers banks the opportunity to borrow from it at the same rate at which it is ready to absorb liquidity. This can be characterised as a corridor with zero width. However, since the floor of the corridor coincides with its ceiling, this approach cannot obviously be qualified as a floor approach. Still the important feature that any desired amount of liquidity is provided when demanded makes this approach akin to a floor one.

6.2 Move to corridor system

The second option is to move back to the corridor approach prevailing before the financial crisis. This is the solution forcefully proposed by Borio (2023). Of course, this would not imply a corridor width of 200 basis points, but it would share the characteristic that no excess liquidity is provided and thus the market rate is not forced to the bottom of the corridor.

6.3 Hybrid

One can blend the two approaches and have a portfolio of assets held for monetary policy purposes to supply liquidity while additional liquidity is provided by standing facilities.

6.4 Complementary options

While the three approaches above identify the main options, many complementary options could characterise a specific operational framework. These are listed and described briefly below. In the next section, they are cross-referenced with the criteria identified in section 4 to assess how different options comply with them.

- Permanent outright portfolio of securities held for monetary policy purposes.The choice to have such a portfolio is implicit in the choice of a floor or a hybrid approach, but important decisions need to be made about its size, duration and composition.

- Long maturity of repo operations.

- Fixed rate full allotment or fixed amount variable rate auctions.

- The width is a critical component of a corridor approach.

- Grant access to lending operations to non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs).

- Grant access to central bank deposits to NBFIs.

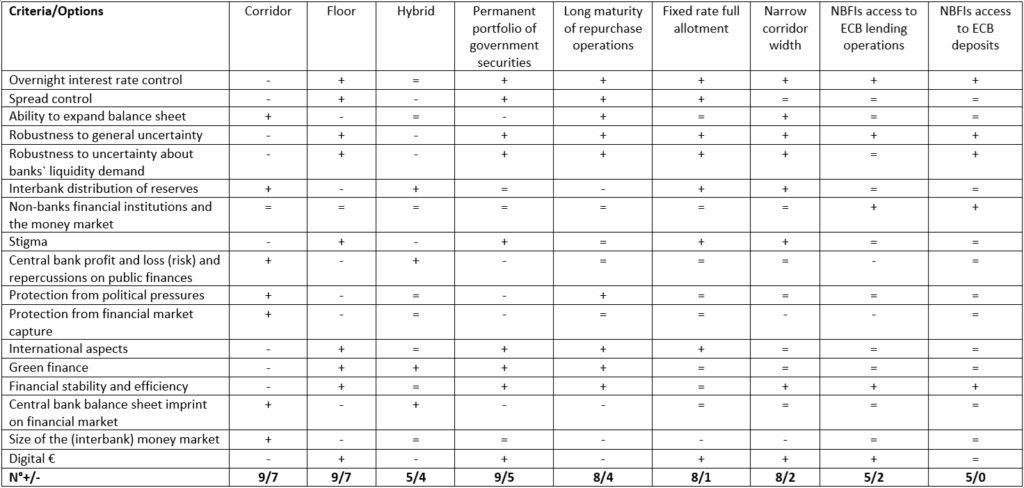

6.5 A matrix approach

To organise in a framework the different options and criteria, we have placed them into the matrix in Table 1, with criteria as rows and options as columns6. A plus (minus) is introduced in the cell if the option has a positive (negative) impact on the criterion, while an equal sign indicates a neutral or uncertain effect.

Of course, judgment is needed to attribute the pluses and the minuses. Furthermore, one could weigh differently the criteria and thus come to a weighted number of pluses and minuses. For instance, the first half of the criteria are arguably more important than the second half. However, one would ask too much from the proposed classification and it is preferable to stay with the following simple conclusions:

- There is no obvious ranking between the corridor, the floor and the hybrid approach, as the minuses and the pluses are too close for this7.

- It is difficult to assess the hybrid approach, which is somewhat amorphous, unless one specifies its characteristics. The hybrid approach is similar to the framework chosen by the ECB in its review, with all its open options.

- A permanent outright portfolio of securities held for monetary policy purposes, long maturities for repo operations, fixed-rate full allotment auctions, a narrow corridor and granting access to deposit facilities to non-banks, all seem to have more advantages than disadvantages.

Table 1: A Matrix approach to criteria and options for an operational framework

Source: Bruegel. Note: + positive; = irrelevant or uncertain; – negative. NBFI = non-bank financial institution.

7 The ECB’s operational framework review

7.1 The content of and gaps in the review

The ECB was confronted with opposing views when reviewing its operational framework: hawks proposed a return to the pre-2008 corridor approach (Borio, 2023), while doves supported the floor approach as a permanent rather than a contingent solution (Constancio, 2018; Reichlin et al, 2024). The ECB eventually chose, after 14 months of deliberations ending in February 2024, a hybrid approach, with both demand and supply components (ECB, 2024). With this choice, the ECB refrained from considering more radical changes to the operational framework, such as those proposed by Bindseil and Würtz (2008), in which it is the liquidity derived from properly structured standing facilities that stabilises the overnight interest rate.

The main components of the new operational framework are:

- The DFR is the main policy rate. At this rate, the ECB, as mentioned above, is willing to absorb any amount of liquidity banks want to deposit.

- Liquidity is provided to banks through two channels: refinancing operations and structural operations.

- Refinancing operations are ‘windows’ at which banks can borrow liquidity from the ECB. The two main refinancing operations are the weekly MRO and the three-month refinancing operations, both conducted at fixed rate and full allotment.

- Structural operations can be divided in two sub-categories: first, the purchase of securities, settled by the ECB crediting liquidity (reserves) to the deposits of the sellers; second, longer-term refinancing operations, giving more stability to the liquidity banks can draw from the ECB’s standing facilities.

- The third, critical component of the new framework is a very narrow corridor: 15 basis points between the MRO rate and the DFR. This should work as a kind of insurance tool: if an unexpected dearth of liquidity risks moving market rates away from the DFR, the possibility to borrow any desired amount from the MRO at a cost close to the DFR should limit the deviation.

Overall, the review has ended up with a system very similar to that proposed by Brandão-Marques and Ratnovski (2024). Demertzis and Papadia (2024) qualified the review as timid because it left some gaps:

- The estimate of excess liquidity to be left in the system.

- The timing of the introduction of the new longer-term lending facilities and of the portfolio of monetary securities.

- The conditions applying to the ECB’s new longer-term lending facilities – for instance their maturity or whether variable or fixed rates will apply.

- The duration and composition of the so-called structural portfolio of securities held for monetary policy purposes.The possible access of non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) to central bank lending or deposit facilities.

- The potential effect of the introduction of a central bank digital currency – the digital euro – on bank liquidity and thus on the provision of liquidity from the ECB.

7.2 More precision would have been unwarranted

Timidity in presenting the new operational framework was justified by the serious uncertainties illustrated above in section 4. More precision could have led to decisions proving suboptimal when the new framework would really have to be implemented. And the lack of precision on some important points is not causing practical problems: the new framework will become relevant only a few years from now, and market participants don’t need to know now how it will work exactly.

8 Features of a new operational framework

The conclusions derived from looking at the options/criteria matrix (Table 1) can help in identifying the features of a new operational framework, thus filling the gaps left by the ECB’s review and helping to better specify the hybrid approach.

8.1 The desirable amount of excess liquidity to be left in the system

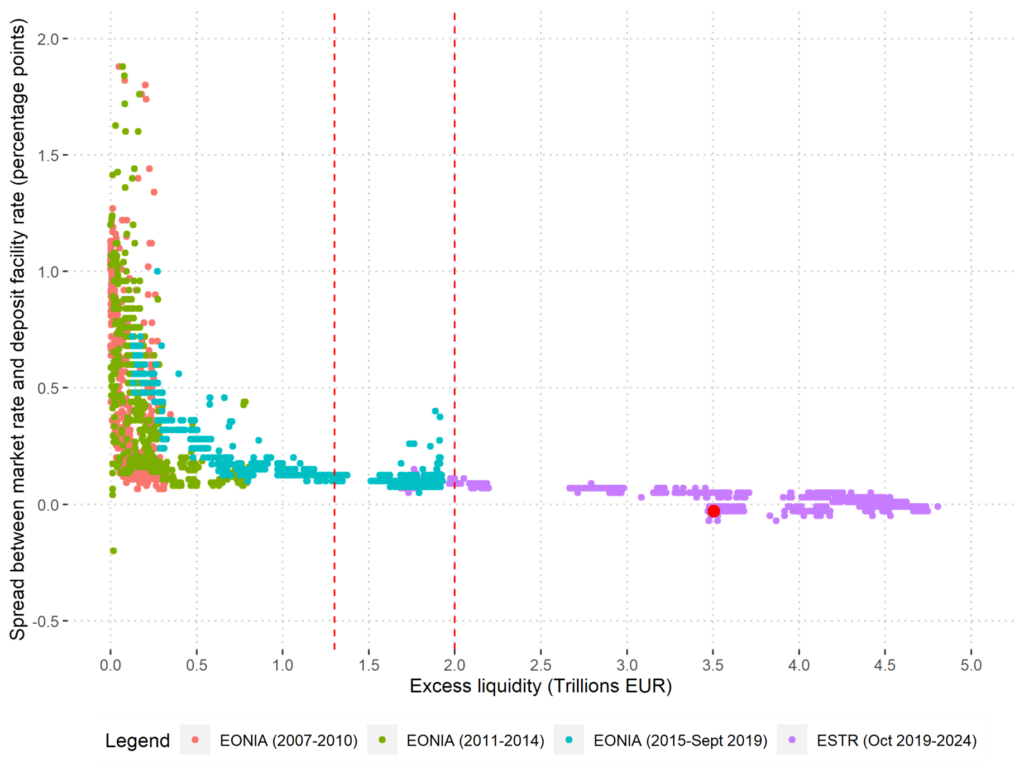

In a first approximation, the take-off point, that is when the overnight rate starts deviating from the DFR, can be estimated in two stages. First, we look at the relationship between excess liquidity and the spread between market rates and the DFR (Figure 8). Specifically, we want to find the level of excess liquidity at which the spread takes off. Then, using balance sheet extrapolations to forecast ECB liabilities, we look at the time corresponding to the designated level of excess liquidity found in the previous step (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Excess liquidity and spread between the relevant overnight rate and the DFR

Source: Bruegel based on ECB data. Note: The red dot represents the level of liquidity as of May 2024.

Figure 9: Extrapolation of the ECB balance sheet, liabilities (€ trillions)

Source: Bruegel based on SMA and ECB data.

Figure 8 shows that the ‘take-off point’ is somewhere close to €1 trillion of excess liquidity, meaning that excess liquidity higher than €1 trillion should still keep the market rate very close to the DFR.

Figure 9 shows that this level of excess liquidity is unlikely to be reached until the end of 2027. So, this analysis shows that a final decision on the approach to take would be needed only a few years from now. Brandão-Marques and Ratnovski (2024) made a different estimate of the take-off point8: €1.3 trillion. Still another estimate was provided by Altavilla et al (2023): 5 percent of bank assets, equivalent to €2 trillion euro. These are the two estimates denoted by the dotted vertical bars in Figures 8 and 9, which would be reached in mid-2027 and March 2026 respectively.

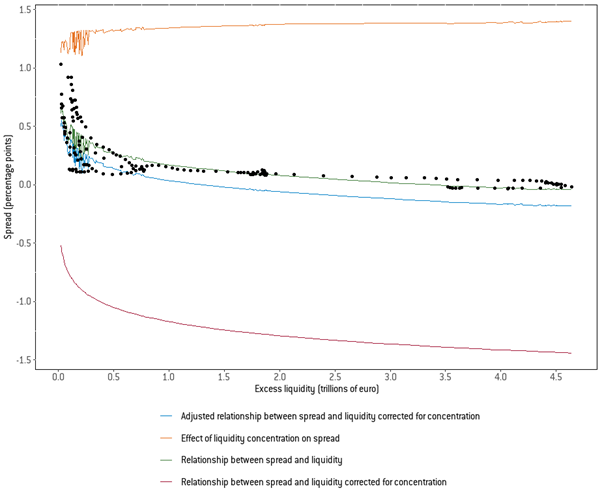

A subtler approach to estimate the take-off point starts from recognising that excess liquidity is distributed very unevenly in the euro area. As documented by Schnabel (2023a), banks in the core of the euro area hold a disproportionate amount of liquidity. As mentioned in section 4, a summary measure of the distribution of excess liquidity is given by so-called TARGET2 balances, reported in Figure 6 in section 4.

The distribution of excess liquidity is important to locate the take-off point because the first banks having recourse to MRO financing should be those less endowed with excess liquidity (Schnabel, 2023a). Thus, the effect of excess liquidity on the spread between the overnight rate and the DFR is less for higher levels of concentration of excess liquidity. In terms of Figure 10, the curve should shift up as liquidity is increasingly concentrated.

To estimate the possible influence of the concentration of liquidity on the spread and thus on the take-off point, a non-linear relationship between the spread and both excess liquidity and liquidity concentration is estimated:

s=f(L,T)9

Where s is the spread between the overnight rate and the DFR, L is excess liquidity and T is TARGET balances (the details of our estimates are in Appendix 1).

Specifically, we estimate the following regression:

s = a + b log(L) + c log(T)

Where we expect b<0 and a>0. Indeed, this is what we find in the regression reported in Appendix 1. However, the estimated coefficient of liquidity concentration (c) is implausibly large, shifting down the spread by close to 1.0 percent across excess liquidity, bringing it into the negative domain. To deal, albeit arbitrarily, with this problem, we reduce the estimated coefficient by 10. In Figure10, the green line interpolates the spread-excess liquidity pairs, the red line is the estimated effect of liquidity concentration, the orange line is the relationship between excess liquidity and the spread net of the effect of concentration, while the blue line is the relationship between liquidity and the spread net of the effect of concentration when the coefficient between the two is reduced by 90 percent. From the blue, last line, one sees that the spread ‘takes off’ from 0 and thus moves away from the DFR for a value of excess liquidity of €1.3 trillion, corresponding to the IMF estimate. We retain this value as our central estimate. We recall that this value will be reached in the middle of 2027.

Figure 10: Relationship between excess liquidity and the spread overnight rate/DFR corrected for liquidity concentration.

Source: Bruegel.

8.2 Longer term refinancing operations

Historically, the longer term refinancing operations had maturities of between three months and four years. The longer maturity proved to be excessive in some cases, as different liquidity and interest rate conditions led banks to repay the funding early. On the other hand, the three-month maturity is probably too short to give confidence to banks about liquidity availability. The addition of LTROs with a maturity of three years, allotted every quarter or every month in addition to the weekly MROs, is probably a good compromise.

As regards the cost of the LTROs, a degree of certainty is useful while not constraining the ability of the ECB to change its interest rates or introducing speculations about ECB interest changes, destabilising demand. To combine these two considerations, full allotment could be combined with a cost derived from the weighted average of the DFR over the duration of the operation. Of course, this would make borrowing from the LTRO cheaper than repeated borrowing granted at the MRO rate. However, applying the MRO rate to the LTROs would inevitably attract market rates towards that level, in contrast with the desire to have the DFR as the policy rate. Still, to reflect the longer maturity, the cost of the LTROs could be increased by a maturity spread derived from the market. So, banks would put forward at auction a demand combined with a quantity and would commit to pay the average of the DFR plus a spread, and all demands would be satisfied.

One issue to be decided is whether the LTROs could have a lower cost if banks commit to using the proceeds for green assets. Many arguments have been made for and against green LTROs, analogous to those made for and against green bonds. While the issue deserves further consideration, it should be recognised that greening LTROs would probably have only a minor effect on the progress towards the climate objectives. First, green LTROs, like green bonds, do not guarantee the greening of economic activity; second, their size is not likely to be large enough to really make a difference. Still, it can be argued that any effort towards achieving the climate objective is helpful, even if not decisive.

8.3 Portfolio of securities

Four factors could determine the maturity of the new portfolio of monetary securities, with the first suggesting a long duration and the other three suggesting a short one:

- Assurance should be given to banks about the horizon of the liquidity they hold;

- A long maturity builds rigidity into the ECB balance sheet;

- While QE worked by ‘extracting maturity’ from the market and thus compressing, through the portfolio balance effect, yields on longer maturities, no such effect is needed when the only objective of a portfolio of monetary policy securities is to provide longer term liquidity to banks;

- Longer-duration assets build interest rate risk in the Eurosystem balance sheet. This must be accepted when the purpose is to ease monetary policy beyond the lower interest rate bound, but no such need exists when no recourse is made to QE because interest rate changes are sufficient to calibrate monetary policy.

Again, as for LTROs, a weighted average duration of three years is a reasonable compromise.

As regards the composition of the portfolio, there is no reason to deviate from the composition of the APP. Thus sovereign, international institutions, corporate, covered bonds and ABS should be in the portfolio, in rough proportion to their importance in the euro-area capital market, pursuing market neutrality (Välimäki and Niemela, 2023).

The ECB capital key should guide the sharing of the sovereign asset portfolio among different countries.

The issue of the greening of the securities in the portfolio has already been addressed by the ECB, especially as regards corporate bonds, and enhanced guidelines could be followed in the future (Välimäki and Niemela, 2023).

8.4 Non-bank financial institutions

In its operational framework review, the ECB paid scant attention to the possible access of non-bank financial institutions to its facilities, just stating that it saw no need for it.

This decision contrasts with the Bank of England, which allows some non-banks to access its balance sheet, and with that of the Fed, as non-banks can, through the so-called reverse repos, deposit liquidity at the Fed in exchange for securities. The rate on these operations is a bit lower than that on reserves deposited by banks but still, indicating the great interest of non-banks, reverse repos have reached very large amounts. The Sveriges Riksbank is considering allowing non-banks to access its balance sheet directly, but it already does so indirectly as it issues short-term bills that can be bought by non-banks.

In favour of the decision to allow non-bank financial institutions to have some form of access to central bank deposits, one can recall that the inability of non-banks to deposit money with the central bank has caused the phenomenon of a so-called ‘leaky floor’, detailed in section 4. Of course, the effect is already decreasing with the withering of excess liquidity, but a leaky floor would remain a vulnerability of the framework.

In addition, it is easier to admit non-banks to deposits than to the central bank funding operations. Banks are tightly regulated and controlled institutions and this protects central banks in their lending operations. Non-banks are, instead, very diverse, less regulated and subject to less-stringent controls. Lending to them would be riskier, on average, than lending to banks.

8.5 Central bank digital currency

The possible issuance of a CBDC is attracting a lot of attention (Bindseil et al, 2024; Armas and Singh, 2022; Tapking et al, 2024). Indeed, giving digital characteristics to central bank money would have important ramifications. The main motivation for this step is to adapt the central bank money held by individuals to the progress in payment systems and, more generally, to IT progress, while assuring strategic independence for the euro area in this crucial domain.

Our perspective on this issue is, however, narrow: we want to explore the possible consequences of the issuance of a digital euro on the ECB’s operational framework10. We will not delve into the pros and cons of such issuance, or the broader possible consequences for the conduct of monetary policy. We also only consider a digital euro as being like a digital version of paper banknotes, with the characteristics the ECB has announced, namely:

- A retail nature, with only physical persons in the euro area allowed to hold it;

- A hard limit on holdings per person, provisionally indicated at €3000;

- No remuneration;

- A ‘waterfall and reverse waterfall’ device, whereby there will be immediate conversion of the digital euro into bank deposits, and vice versa, whenever a transaction would cause a store of digital euros to exceed the maximum holding, or to become negative.

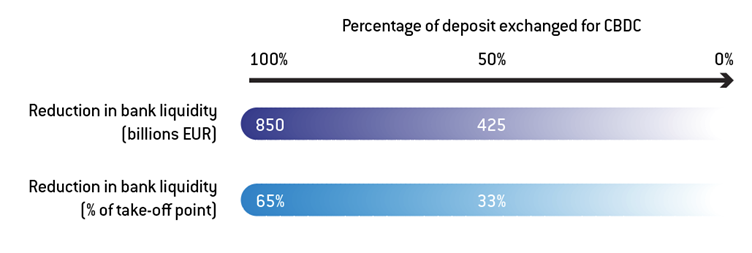

From our point of view, the question is whether the issuance of a digital euro can have effects on central bank reserves held by banks: if individuals hold digital euros fully as a substitute for bank deposits, the liquidity of banks would decrease one-for-one with each issued digital euro. If, instead, they would hold digital euros fully as a substitute for banknotes, then there would be no effect on bank liquidity (Bindseil and Senner, 2024; Brandão-Marques and Ratnovski, 2024).

Figure 11 illustrates the issue. On the left of the axis in the figure, the reduction in bank liquidity, €850 billion, corresponds to the maximum amount of digital euro holdings, ie €3000 multiplied by the number of adults in the euro area (284 million in 2023 according to Eurostat). This limit would be reached if individuals were to fully substitute bank deposits with digital euros, and would correspond to about two thirds of the liquidity we estimated would prevail when the take-off is reached. As one moves from left to right, the percentage of bank deposits exchanged for digital euros drops and, correspondingly, the percentage exchanged for banknotes goes up. If digital euros were exchanged 50 percent for bank deposits, the reduction of bank liquidity would be €425 billion, corresponding to about one third of the liquidity prevailing at the take-off point. At the extreme right of the axis, all digital euros are exchanged for banknotes and there is no effect on bank liquidity.

Figure 11: Potential effects of the introduction of a CBDC on bank liquidity

Source: Bruegel calculation based on Eurostat and ECB data.

Given the theoretical extremes of 100 percent and 0 percent for the exchange of bank deposits for digital euros represented in Figure 11, one issue is where the percentage will be. Another one, more important, question is under what conditions could the percentage move from bank deposits to digital euros.

Bindseil and Senner (2024) insisted that, given the four characteristics listed above for the digital euro, the amount of circulating digital euros should be limited and therefore the reduction in bank deposits and reserves should also be limited and manageable. Thus, reality should settle in the area close the right of the axis (Figure 11). In other words, the digital euro is a close substitute for banknotes and as central banks have managed to deal with the shocks of liquidity imparted by changes in banknote circulation, also in crisis periods, so they will be able to deal with the effects of changes in digital euro holdings.

Tapking et al (2024) take a less-assured view, noting that there are indeed differences between digital euros and banknotes in terms of withdrawal ease, storage cost, privacy and theft risk. They note that there could be shifts from bank deposits to digital euros in case of fears about the safety of bank deposits. Uncertainty about possible shifts between bank deposits and digital euros is likely to increase the precautionary demand for liquidity from banks, to be ready to accommodate these shifts without problems. Based on the analysis in Tapking et al (2024), one can conclude that the shocks to bank reserves that could follow the introduction of a digital euros are not the same as those prevailing when only banknotes are available to the public. One can add that the absence of experience with the introduction of a CBDC will introduce an additional layer of uncertainty: while the demand for banknotes has been estimated using very long time series, behaviour in terms of demand for digital euros will remain unknown for a long time.

The qualitative conclusion from the considerations above is that the introduction of a digital euro will most likely require a higher buffer in the supply of reserves from the ECB and, more importantly, flexibility in offsetting shocks to liquidity from shifts in and out of digital euros.

It is much more difficult to come to a quantitative conclusion. One preliminary indication is that prudently the ECB could increase the liquidity maintained in the system with respect to our estimate prevailing at the take-off point.

8.6 Conclusions

The hybrid approach chosen by the ECB has an intrinsic ambiguity: the DFR should remain the policy rate, while at the same time, the role of the MRO rate is underlined by the decision that “Main refinancing operations (MROs) [must] play a central role in meeting banks’ liquidity needs” (ECB, 2024). The solution to this ambiguity should come in 2026 when the gaps left by the review will be filled.

The features that we propose to give more precision to the hybrid approach lead to a system very close to the floor one. Indeed, we propose to maintain a relatively large amount of excess liquidity in the system to avoid the overnight rate ‘taking off’ from the DFR. We also suggest relatively generous maturity and cost of Longer Term Refinancing Operations and we think it is prudent that the provision of excess liquidity is ample enough to take into account the possible liquidity effects of the introduction of a digital euro.

Different choices could tilt the system towards a ceiling approach, where the rate tends to be close to the MRO rate. The difference between the two, 15 basis points in the ECB decision, is small but significant, considering the keen attention the ECB Governing Council and market participants give to the standard 25 basis-points interest rate changes. In addition, the width of the corridor will not necessarily always remain so narrow, thus the difference between the two approaches could get larger over time.

In any case, the parameters of the framework could be calibrated as experience accumulates, and it could be tilted away, with practically any desired degree of granularity, from mimicking the floor approach to a system closer to the floor approach.

References

Altavilla, C., M. Rostagno and J. Schumacher (2023) ‘Anchoring QT: Liquidity, credit and monetary policy implementation’, Discussion Paper DP18581, Centre for Economic Policy Research, available at https://cepr.org/publications/dp18581

Armas, A. and M. Singh (2022) ‘Digital Money and Central Banks Balance Sheet’, IMF Working Paper No. 2022/206, International Monetary Fund, available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/10/28/Digital-Money-and-Central-Banks-Balance-Sheet-524987

Bindseil, U. and F.R. Würtz (2008) ‘Efficient and Universal Frameworks (EUF) for Monetary Policy Implementation’, mimeo, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4465338

Bindseil, U., P. Cipollone and J. Schaaf (2024) ‘The digital euro after the investigation phase: Demystifying fears about bank disintermediation’, VoxEU, 19 February, available at https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/digital-euro-after-investigation-phase-demystifying-fears-about-bank

Bindseil, U., and R. Senner (2024) ‘Macroeconomic modelling of CBDC: a critical review’, mimeo, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=4782993

Borio, C. (2023) ‘Getting up from the floor’, BIS Working Paper No. 1100, Bank for International Settlements, available at https://www.bis.org/publ/work1100.pdf

Borio, C., P. Disyatat and A. Schrimpf (2024) ‘The double-faced demand for bank reserves and its implications’, VoxEU, 15 February, available at https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/double-faced-demand-bank-reserves-and-its-implications

Brand, C., N. Lisack and F. Mazelis (2024) ‘Estimates of the natural interest rate for the euro area: an update’, ECB Economic Bulletin 1/2024, European Central Bank, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2024/html/ecb.ebbox202401_07~72edc611d3.en.html

Brandão-Marques, L. and L. Ratnovski (2024) ‘The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework: Corridor or Floor?’, IMF Working Paper No. 2024/056, International Monetary Fund, available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2024/03/15/The-ECBs-Future-Monetary-Policy-Operational-Framework-Corridor-or-Floor-546355

Chiacchio, F., G. Claeys and F. Papadia (2018) ‘Should we care about central bank profits?’ Policy Contribution 13/2018, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/should-we-care-about-central-bank-profits

Constancio, V. (2018) ‘Past and future of the ECB monetary policy’, speech to the Conference on ‘Central Banks in Historical Perspective: What Changed After the Financial Crisis?’, organised by the Central Bank of Malta, Valletta, 4 May, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2018/html/ecb.sp180504.en.html

Demertzis, M. and F. Papadia (2024) ‘The European Central Bank’s timid operational framework update’, First Glance, 14 March, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/first-glance/european-central-banks-timid-operational-framework-update

ECB (2001) Monthly Bulletin, July 2001, European Central Bank, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/mobu/mb200107en.pdf

ECB (2015) ‘The role of the central bank balance sheet in monetary policy’, Economic Bulletin 4/2015, European Central Bank, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/art01_eb201504.en.pdf

ECB (2024) ‘Changes to the operational framework for implementing monetary policy’, Statement by the Governing Council, 13 March, European Central Bank, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2024/html/ecb.pr240313~807e240020.en.html

Friedman, B. and K. Kuttner (2010) ‘Implementation of Monetary Policy: How Do Central Banks Set Interest Rates?’ NBER Working Paper 16165, National Bureau of Economic Research, available at https://doi.org/10.3386/w16165

Hartmann, P. and F. Smets (2018) ‘The First Twenty Years of the European Central Bank: Monetary Policy’, ECB Working Paper No 2219, European Central Bank, available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3309645

Hauser, A. (2019) ‘Waiting for the exit: QT and the Bank of England’s long-term balance sheet’, speech given at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London, 17 July, Bank of England, available at https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2019/andrew-hauser-speech-hosted-by-the-afme-isda-icma-london

Mercier, P. and F. Papadia (eds) (2011) The Concrete Euro: Implementing Monetary Policy in the Euro Area, Oxford University Press

Mongelli, F.P. and G. Camba-Mendez (2018) ‘The Financial Crisis and Policy Responses in Europe (2007–2018)’, Comparative Economic Studies 60(4): 531–58, available at https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0074-4

Papadia, F. and T. Välimäki (2018) Central Banking in Turbulent Times, Oxford University Press, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198806196.001.0001

Reichlin, L., G. Ricco and M. Tarbé (2023) ‘Monetary–fiscal crosswinds in the European Monetary Union’, European Economic Review 151: 104328, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292122002082

Reichlin, L., J. Pisani-Ferry and J. Zettelmeyer (2024) The Euro at 25: Fit for purpose?, Study requested by the ECON Committee, European Parliament, available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2024)747834

Schnabel, I. (2023a) ‘Back to normal? Balance sheet size and interest rate control’, speech at an event organised by Columbia University and SGH Macro Advisors, 27 March, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2023/html/ecb.sp230327_1~fe4adb3e9b.en.html

Schnabel, I. (2023b) ‘Monetary and financial stability – can they be separated?’ speech to the Conference on Financial Stability and Monetary Policy in the honour of Charles Goodhart, 19 May, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2023/html/ecb.sp230519~de2f790b1c.en.html

Schnabel, I. (2024) ‘The Eurosystem’s operational framework’, speech at the Money Market Contact Group meeting, 14 March, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2024/html/ecb.sp240314~8b609de772.en.html

Tapking, J., T. Vlassopoulos and E. Caccia (2024) ‘Central Bank Digital Currency and Monetary Policy Implementation’, ECB Working Paper No 2024/345, European Central Bank, available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4795549

Trichet, J.-C. (2008) ‘Some lessons from the financial market correction’, speech to the European Banker of the Year 2007 award ceremony, Frankfurt am Main, 30 September, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2008/html/sp080930_1.en.html

Trichet, J.-C. (2009) ‘The ECB’s enhanced credit support’, speech at the University of Munich, 13 July, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2009/html/sp090713.en.html

Välimäki, T. and J. Niemela (2023) ‘Back to the old normal? Monetary policy implementation in a landscape of rising interest rates and a shrinking Eurosystem balance sheet’, Bank of Finland Bulletin, 7 September, Bank of Finland, available at https://www.bofbulletin.fi/en/2023/3/back-to-the-old-normal-monetary-policy-implementation-in-a-landscape-of-rising-interest-rates-and-a-shrinking-eurosystem-balance-sheet

Veron, N. (2024) Europe’s Banking Union at Ten: Unfinished yet Transformative, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/book/europes-banking-union-ten-unfinished-yet-transformative

Appendix 1 – The effect of liquidity concentration

Data

In the paper, we argue that if liquidity is concentrated in some banks its effect on the spread between the market rate and the DFR is attenuated. Thus, to estimate the minimum level of excess liquidity needed to avoid the market rate ‘taking off’ from the DFR, a measure of concentration is needed. Once we have estimated the minimum excess liquidity at the take-off point, we check when the time region corresponding to that level of excess liquidity is reached. The following paragraphs explain our estimates.

Concentration

As a synthetic measure of concentration, TARGET2 balances were considered. The two countries with the highest balances, Germany and Luxembourg, were grouped as the ‘Core’, while the two with the lowest balances, Italy and Spain, were grouped as the ‘Periphery’. The sum of the absolute values of balances for these groups was then computed. This sum is the measure of concentration used in the analysis.

Excess liquidity

To forecast the values of excess liquidity, the data underlying Schnabel (2023a), and kindly provided by the ECB, is used. This dataset projects the ECB balance sheet with monthly frequency up to end 2025. To extrapolate the data, projections on total assets until 2030 are first recovered. Then, by subtracting estimates of liabilities items from the total assets, the value of excess liquidity is determined.

The projections of the ECB assets starting from 2026 are based on the Survey of Monetary Analysts (SMA) in the April 2024 version. In the SMA, analysts provide their expectations on the asset side of the ECB balance sheet, specifically on MRO, LTRO, TLTRO, APP, and PEPP. For MRO and LTRO, data are available quarterly until 2026Q4, and we assume linear growth thereafter. For TLTRO, the quarterly data stop at 2024Q3, and a value of zero is assumed thereafter. For APP and PEPP, quarterly data are available until 2027Q4, followed by annual data. Based on these assumptions, total assets are computed as the sum of the five items and the series is extended to 2030 using the median expectation values. To align the total assets derived from the SMA with the series in Schnabel (2023a), the series from Schnabel (2023a) was adjusted by incorporating the first difference of the SMA projections. This adjustment allows the Schnabel series to grow in accordance with the SMA projections from 2026 to 2030.

On the liability side, as no information is available in the SMA, projections from Schnabel (2023a) are used, with a linear interpolation of the following items: banknotes, official government deposits and minimum reserves. By subtracting these from the total liabilities (which are by definition equal to total assets), the excess liquidity is determined.

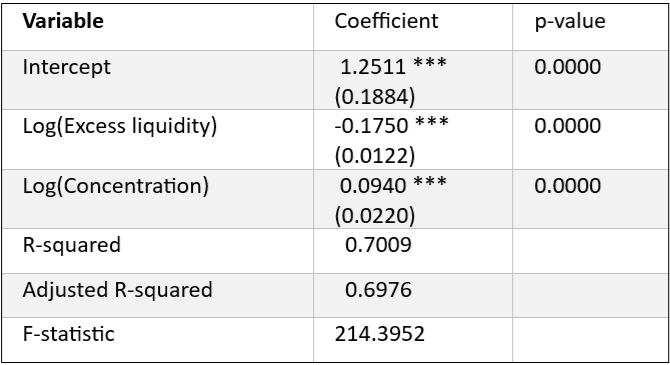

Regression results

The table below contains the regression results from the equation:

s=f(L,T)

in the form:

s = a + b Log(Excess Liquidity) + c Log(Concentration) + e

Where s is the normalised spread between market rate (EONIA before oct 2019, then €STR11) and DFR computed as (market rate-DFR)/(market rate – MROr). As explained above, concentration is a measure of target balances sum and excess liquidity is defined as the amount of liquidity held in the current accounts or at the deposit facility net in excess of compulsory reserves. The series run from September 2008 to February 2024. The regression coefficients read:

Notes: Standard errors in brackets, *** = p-value <0.001, **= p-value <0.01, * = p-value <0.05

Appendix 2 – Comparing the elasticities of balance sheet changes and interest rates changes on inflation