Pondered reflections on the Jackson Hole Symposium.

The Jackson Hole symposium, organized by the Kansas City Federal Reserve, took place between the 25th and the 27th of August 2016. This is the most important gathering dedicated to longer term and analytical considerations about central banking. The Sintra ECB Forum on Central Banking comes second, just as the euro is the second most important global currency after the dollar.

Notwithstanding the desire to move away from contingent issues, markets and media have dedicated an overwhelming attention to three lines proffered by the FED Chair Janet Yellen, among the thousands that were offered at the symposium: “Indeed, in light of the continued solid performance of the labor market and our outlook for economic activity and inflation, I believe the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months.”

I am sure the FED Chair was aware that media and market attention would concentrate on those three lines to extract information on whether the FED would increase rates at the September or at the December meeting. Still the reason of this overwhelming concentration on that message remains somewhat mysterious to me. Basically, I believe it makes no economic difference whether the FED would increase rates in September or in December.

Mysterious as it may be, the overemphasis on the short Yellen message is a fact and I have no pretence to change it. Still, in this post I would like to cover another two, longer term, issues that were discussed in Jackson Hole:

• Will the changes in the framework for implementing monetary policy enacted during the Great Recession survive it?

• What would be the possible impact on current conditions from a change in central bank inflation targets?

The two issues are examined in turn.

First question: Will changes in the implementation of monetary policy enacted during the Great Recession survive it?

The answer that my co-authors and I gave to this question back in 2011 1 was mixed: no change in the operational objective, namely a short term rate, and a preference for a return to a lean central bank balance sheet were the most important aspect of the “return to pre-2007” approach. New ways to steer short-term rates were seen as the likely most important innovation going forward. Basic uncertainty was expressed, however, whether a “Broad” or a “Narrow” approach for collateral and counterparties would be preferable once the crisis would be surpassed.

My reading of five papers presented at Jackson Hole 2 is that, five years after 2011, more of the changes enacted during the crisis will survive it.

Possibly the most important change with respect to the view expressed in 2011 is about the size of the central banks balance sheets. The consensus in 2016 is that central bank balance sheets will remain, for the foreseeable future, much larger than the pre-2007 trend would have implied. 3 This consensus, however, is part of a more general move towards a “broader” operational framework, i.e. one with a wider collateral, more ample provision of liquidity, also through permanent operations, and an interest target which does not concentrate only on the shortest rates, i.e. on the hinge of the yield curve, but looks at the entire curve.

The move of the FED from a narrow to a broad approach is implicit in the contrast presented by Yellen between the “simple, light-touch system” prevailing before the crisis and the expectation that “asset purchases will remain important components of the Fed’s policy toolkit.“

Potter is even more explicit when doubting the conclusion reached by Bindseil (see below) about the desirability of a lean balance sheet.

Coeuré expects that “Unconventional policies may have to be deployed more often.” He also supports the idea that it would be preferable to maintain the wider collateral framework and fixed rate full allotment adopted during the crisis. He even advances the hypothesis that: “the quantity of liquidity to be supplied could become a quasi-intermediate target almost on a par with the level of the policy rate. But then we could not rely solely on “passive” lending operations to deliver the right stance of policy: we would need a more active instrument to inject the “right” quantity of reserves.” The instrument to which Coeuré alludes is obviously QE. The conclusion consistent with these statements is that the central bank balance sheet will have to remain larger than the pre-2007 pattern would have implied.

Danthine does not provide a general normative statement but expresses more of a positive view that: “ …there is no guarantee that future economic conditions will permit adopting a monetary strategy consistent with a significant decrease of the SNB’s balance sheet, at least in the near or medium term, even if this was unanimously desired.”

Bindseil does express a preference for a lean balance sheet: “While in crisis times, there are a number of justifications for lengthening the central bank balance sheet …, a lean balance sheet is in principle positive in normal times as it suggests that the central bank focuses on the core of its mandate. …the idea that the central bank permanently injects monetary accommodation through a longer balance sheet with substantial holdings … of less liquid assets … does not appear sufficiently convincing.

In addition, it seems clear that variations of outright portfolio size and composition should not be considered as tool for varying the stance of monetary policy over time. Adjusting short term interest rates should be the only tool for that purpose in normal times.” However, the stress on “normal times” shows that the horizon over which it will be possible to get back to a lean balance sheet is only in the distant future. Indeed Bindseil expects: ” … a higher likelihood that the zero‐lower bound (“ZLB”) for short‐term interest rates will be in the future a recurring constraint to monetary policy.” An expectation implying the continued use of QE necessarily implies a large balance sheet for quite some time.

In conclusion, the overall answer that can be given to the first question listed above is as follows. Before the crisis, T. Välimäki and I4 defined the FED operational framework as “narrow” (few counterparties, small operations, relatively homogeneous collateral) and that of the ECB as “broad” (many counterparties, heterogeneous collateral, large operations). We also showed that, before the crisis, there was little ground to choose between the two approaches. The broad approach, however, proved more robust during the crisis and the FED clearly moved in this direction while the ECB further broadened its approach. Now the expectation is that the general broadening of the approach enacted during the crisis will remain for the foreseeable future both in the US and in the €-area. The time when central banks will be able to move back to their important but specific niche in the money market is, unfortunately in my view, quite far into the future

Second question: Can a change in the inflation target of the central bank have an immediate easing impact?

One can conceive three possible hard changes:

1. Increase the inflation target,

2. Move to a price level target

3. Move to a nominal GDP target.

But there are also softer versions of these changes:

1. Communicate that inflation higher than 2% will be tolerated for a while,

2. Recall that (undefined) medium term horizon does not require over reacting to short-term inflation developments.

The question addressed here is not whether changes, be they hard or soft, would be desirable on a regime basis, which is an important topic in itself. The issue is whether these changes would have an immediate easing impact, possibly contributing to relieve the constraint given by the interest rate lower bound, which until recently was more precisely, but wrongly, denominated as the zero lower bound. The practical relevance of this question derives from the fact that available quotations from FED and ECB representatives show that, while a hard change is not considered, at least for the time being, there are hints of possible soft changes.

FED

John Williams, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, is not yet pressing for a change in the target—he’s merely asking for it to be considered. “although targeting a low inflation rate generally has been successful at taming inflation in the past, it is not as well-suited for a low r-star era. There is simply not enough room for central banks to cut interest rates in response to an economic downturn when both natural rates and inflation are very low.

Two alternatives can be considered together or in isolation to address this issue. First, the most direct attack on low r-star would be for central banks to pursue a somewhat higher inflation target. … Second, inflation targeting could be replaced by a flexible price-level or nominal GDP targeting framework, where the central bank targets a steadily growing level of prices or nominal GDP, rather than the rate of inflation. … Of course, these approaches also have potential disadvantages and must be carefully scrutinized when considering their relative costs and benefits.”

Janet Yellen: “some observers have suggested raising the FOMC’s 2 percent inflation objective or implementing policy through alternative monetary policy frameworks, such as price-level or nominal GDP targeting. I should stress, however, that the FOMC is not actively considering these additional tools and policy frameworks, although they are important subjects for research.”

ECB

Mario Draghi said, quasi en passant, in November 2015 : “In making our assessment of the risks to price stability, we will not ignore the fact that inflation has already been low for some time.”

Victor Constancio followed up in an interview for Boersen Zeitung, in which he ruled out any price-level targeting, but did not exclude a soft change:

“President Draghi said at the start of December that, in the future, the Governing Council will have to take into account the fact that inflation has been well below 2% for a long time. This reminded some of the idea of price-level targeting, whereby if a target is missed, that shortfall must be made up for later. Is a rethink on the horizon? That is certainly one of the over-interpretations which I mentioned earlier. I would never agree to price-level targeting. That is also not a consideration for us.”

Peter Praet added: “the argument that central banks can tolerate periods of too-low inflation is correct. Inflation can move temporarily below – or above – our aim without requiring an immediate policy response.”

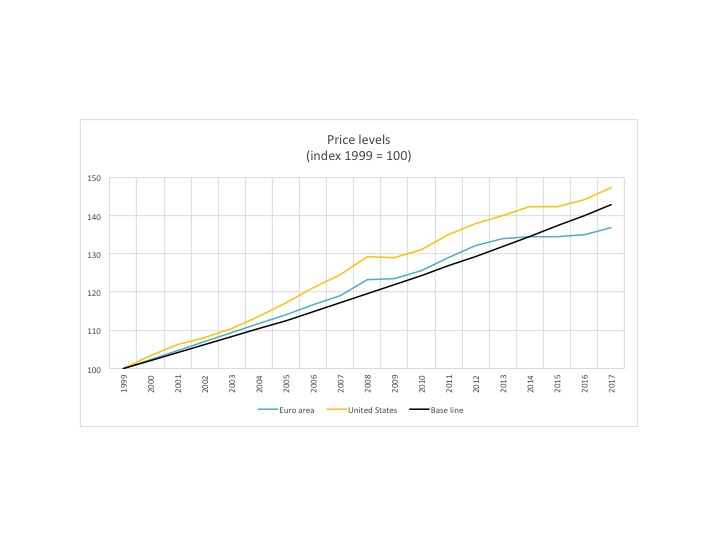

In order to assess the possible impact of a change in the central bank target, probably a soft one rather than a hard one given the quotations above, it is useful to see which difference a price level and a GDP level target would have made. This is done in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Price level vs. inflation target.

Source: AMECO, estimates start in 2016. Note: For the price levels we use the national definition of the consumer price index, with base year in 1999. The base line is a theoretical price level with 2 per cent annual inflation.

Source: AMECO, estimates start in 2016. Note: For the price levels we use the national definition of the consumer price index, with base year in 1999. The base line is a theoretical price level with 2 per cent annual inflation.

Figure 1 shows that the FED has accumulated over the years an over-run with respect to a CPI target resulting from a 2 per cent per annum inflation.

On the contrary, the ECB has accumulated over the last 3 years a significant under-run.

Of course, both the FED over-run and the ECB under-run are relative to an arbitrary 1999 basis. The conclusions would be different if a different base year was chosen and the degree of arbitrariness that is introduced by the necessary choice of a base year is one of the weaknesses of a price level (or a GDP level) target.

In any case, the “memory” which is implicit in a price level target would imply that the FED should now tighten quite significantly its monetary policy and aim for rates of inflation lower than 2 per cent over the coming years (specifically 1.4 per cent annually over a 5 year horizon) to compensate for the over-accumulated inflation, in particular between 1999 and 2008. The ECB, instead, should aim for quite some time at a rate of inflation higher than 2 per cent. For example, if it wanted to recover the undershooting of inflation over a 5-year horizon it should achieve a 3 per cent inflation on average.

Figure 2 carries out an analogous exercise to figure 1 but the target here is a GDP level increasing by a constant 4 per cent (the 4 per cent growth can be thought as resulting from 2 per cent inflation and 2 per cent real growth).

Figure 2. GDP level vs. inflation target.

Source: IMF WEO for the US and AMECO for the Euro area, estimates start in 2016. Note: The base line represents a constant 4 % annual growth rate.

Source: IMF WEO for the US and AMECO for the Euro area, estimates start in 2016. Note: The base line represents a constant 4 % annual growth rate.

In this case the FED is just on target, and thus would have no reason to over or under achieve a 4 per cent nominal GDP growth in the following years. The ECB would, instead, be well below the target, because the undershoot of inflation adds itself to the undershoot on real growth. If the ECB wanted to get back to the 4 per cent growth line it would have to achieve a 8 per cent annual growth of nominal GDP in the next 5 years.

The practical conclusion one can draw from Figures 1 and 2 is that moving to a price level or a GDP level target would not imply an easier policy for the FED. On the contrary the easing of policy that would be implied for the ECB would be unrealistic, especially for a GDP target.

Whatever difference a price level or nominal GDP target would make for the FED and the ECB, one can ask why would a change in the target have an immediate effect.

The mechanism is here through expectations: if the promise of an easier policy after the inflation target of 2 per cent would be achieved was credible, the expectations component of longer rates would come down and this would have an easing impact. The transmission channel is thus the same as forward guidance. The transmission channel is also contiguous to that of QE, which also works on longer rates, but mostly on the term premium.

The next practical question is whether the effect of a promise of easier policy in the future can add itself to that of QE and forward guidance, which the ECB, in particular, is still pursuing in earnest and has arguably already compressed the yield curve(s) in the €-area.

A look at the yield curve in the US and, in particular, the €-area can give some information in this respect.

Figure 3. Yield curve US and €-area (Germany and Italy).

Source: US Treasury data and Bloomberg, data as of September 2016.

Source: US Treasury data and Bloomberg, data as of September 2016.

Given the very flat yield curve in the €-area (taking the German and the Italian curves as representative of the core and the periphery respectively) there does not seem to be much room for the promise of future easing to have an impact on current conditions: the German yield curve is negative up to the 10 years maturity and also the Italian curve is negative up to 3 years maturity. In addition, it is not clear why any additional flattening of the curve that would be desired should be obtained by a change of the inflation target, which would then persist over time and have possibly undesired consequences, rather than with forward guidance or, arguably more effectively, through additional QE.

Overall the following answer to the second question previously listed may be drawn from the simple analysis above:

• In the US a hard switch from an inflation to a price level or a nominal GDP target would not plausibly lead to a more accommodation policy in the future.

• A similar switch in the €-area would be unrealistic and probably not be credible.

• In any case, the flat yield curve, particularly in the €-area, does not leave much room for an expectation of future easing to impact on current yields.

• It is not clear that any additional flattening of the yield curve would be better achieved changing the inflation target rather than by additional QE.

• A “soft” version of the move to a price level target, especially in the form of recognizing that it would not be opportune to react too hastily and too brutally to a move of inflation beyond 2 per cent, after more than 3 years in which it has been well below target, is possible, but would likely have an even more modest effect on the current policy stance.

This post was prepared with the assistance of Pia Hüttl.

- Mercier and Papadia eds. The Concrete euro, Implementing Monetary Policy in the Euro Area. Oxford University Press, 2011.[↩]

- The five papers cover the views of 3 advanced economies central banks: the FED, the ECB and the Swiss National Bank. Janet Yellen, Opening Remarks of Session on Evaluating Alternative Monetary Frameworks. Ulrich Bindseil, Paper on: Evaluating Monetary Policy Operational Frameworks. J.P. Danthine, Comments on: Evaluating Monetary Policy Frameworks. S. Potter, Comments on: Evaluating Monetary Policy Frameworks. B. Coeuré, Panel Intervention on: Evaluating Monetary Policy Frameworks.[↩]

- I was also forced to admit that the prospects of the normalization of the size of the balance sheets of the FED and the ECB are probably to be postponed at least to 2023 and 2028 respectively: “How should central banks steer money market interest rates?”, Presentation prepared for the Columbia-SIPA FED NY Conference on “Implementing Monetary Policy Post-Crisis – What Have We Learned? What Do We Need To Know? May 4th 2016.[↩]

- Again in the Concrete Euro.[↩]